NAMES

TAXONOMY

South Africa

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

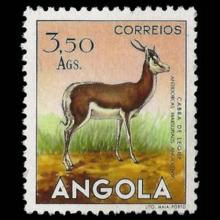

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

South Africa

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

South Africa

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

South Africa

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

South Africa

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

South Africa

Issued:

Stamp:

Antidorcas marsupialis

Genus species (Animalia): Antidorcas marsupialis

The springbok or springbuck (Antidorcas marsupialis) is an antelope found mainly in south and southwest Africa. The sole member of the genus Antidorcas, this bovid was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann in 1780. Three subspecies are identified. A slender, long-legged antelope, the springbok reaches 71 to 86 cm (28 to 34 in) at the shoulder and weighs between 27 and 42 kg (60 and 93 lb). Both sexes have a pair of black, 35-to-50 cm (14-to-20 in) long horns that curve backwards. The springbok is characterized by a white face, a dark stripe running from the eyes to the mouth, a light-brown coat marked by a reddish-brown stripe that runs from the upper fore leg to the buttocks across the flanks like the Thomson's gazelle, and a white rump flap.

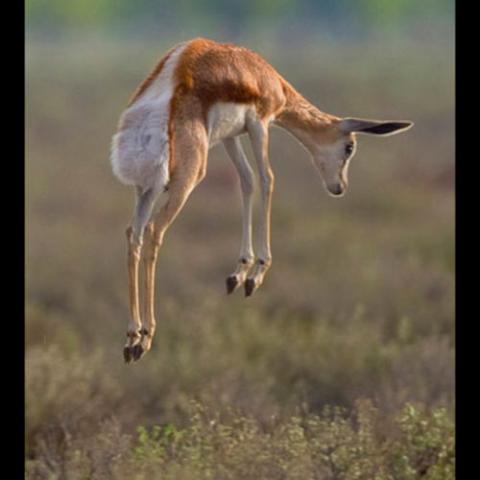

Active mainly at dawn and dusk, springbok form harems (mixed-sex herds). In earlier times, springbok of the Kalahari desert and Karoo migrated in large numbers across the countryside, a practice known as trekbokking. A feature, peculiar but not unique, to the springbok is pronking, in which the springbok performs multiple leaps into the air, up to 2 m (6.6 ft) above the ground, in a stiff-legged posture, with the back bowed and the white flap lifted. Primarily a browser, the springbok feeds on shrubs and succulents; this antelope can live without drinking water for years, meeting its requirements through eating succulent vegetation. Breeding takes place year-round, and peaks in the rainy season, when forage is most abundant. A single calf is born after a five- to six-month-long pregnancy; weaning occurs at nearly six months of age, and the calf leaves its mother a few months later.

Springbok inhabit the dry areas of south and southwestern Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources classifies the springbok as a least concern species. No major threats to the long-term survival of the species are known; the springbok, in fact, is one of the few antelope species considered to have an expanding population. They are popular game animals, and are valued for their meat and skin. The springbok is the national animal of South Africa.

Entymology

The common name "springbok", first recorded in 1775, comes from the Afrikaans words spring ("jump") and bok ("antelope" or "goat"). The scientific name of the springbok is Antidorcas marsupialis. Anti is Greek for "opposite", and dorcas for "gazelle" – identifying the animal as not a gazelle. The specific epithet marsupialis comes from the Latin marsupium ("pocket"), and refers to a pocket-like skin flap which extends along the midline of the back from the tail, which distinguishes the springbok from true gazelles.

Taxonomy and evolution

The springbok, in the family Bovidae, was first described by the German zoologist Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann in 1780, who assigned the genus Antilope (blackbuck) to the springbok. In 1845, Swedish zoologist Carl Jakob Sundevall placed the springbok as the sole living member of the genus Antidorcas.

Evolution

Fossil springbok are known from the Pliocene; the antelope appears to have evolved about three million years ago from a gazelle-like ancestor. Three fossil species of Antidorcas have been identified, in addition to the extant form, and appear to have been widespread across Africa. Two of these, A. bondi and A. australis, became extinct around 7,000 years ago (early Holocene). The third species, A. recki, probably gave rise to the extant form A. marsupialis during the Pleistocene, about 100,000 years ago. Fossils have been reported from Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene sites in northern, southern, and eastern Africa. Fossils dating back to 80 and 100 thousand years ago have been excavated at Herolds Bay Cave (Western Cape Province, South Africa) and Florisbad (Free State), respectively.

Description

The springbok is a slender antelope with long legs and neck. Both sexes reach 71–86 cm (28–34 in) at the shoulder with a head-and-body length typically between 120 and 150 cm (47 and 59 in).[2] The weights for both sexes range between 27 and 42 kg (60 and 93 lb). The tail, 14 to 28 cm (5.5 to 11.0 in) long, ends in a short, black tuft.[2][10] Major differences in the size and weight of the subspecies are seen. A study tabulated average body measurements for the three subspecies. A. m. angolensis males stand 84 cm (33 in) tall at the shoulder, while females are 81 cm (32 in) tall. The males weigh around 31 kg (68 lb), while the females weigh 32 kg (71 lb). A. m. hofmeyri is the largest subspecies; males are nearly 86 cm (34 in) tall, and the notably shorter females are 71 cm (28 in) tall. The males, weighing 42 kg (93 lb), are heavier than females, that weigh 35 kg (77 lb). However, A. m. marsupialis is the smallest subspecies; males are 75 cm (30 in) tall and females 72 cm (28 in) tall. Average weight of males is 31 kg (68 lb), while for females it is 27 kg (60 lb). Another study showed a strong correlation between the availability of winter dietary protein and the body mass.

Dark stripes extend across the white face, from the corner of the eyes to the mouth. A dark patch marks the forehead. In juveniles, the stripes and the patch are light brown. The ears, narrow and pointed, measure 15–19 cm (5.9–7.5 in). Typically light brown, the springbok has a dark reddish-brown band running horizontally from the upper foreleg to the edge of the buttocks, separating the dark back from the white underbelly. The tail (except the terminal black tuft), buttocks, the insides of the legs and the rump are all white. Two other varieties – pure black and pure white forms – are artificially selected in some South African ranches. Though born with a deep black sheen, adult black springbok are two shades of chocolate-brown and develop a white marking on the face as they mature. White springbok, as the name suggests, are predominantly white with a light tan stripe on the flanks.

Ecology and behavior

Springbok are mainly active around dawn and dusk. Activity is influenced by weather; springbok can feed at night in hot weather, and at midday in colder months. They rest in the shade of trees or bushes, and often bed down in the open when weather is cooler.

The social structure of the springbok is similar to that of Thomson's gazelle. Mixed-sex herds or harems have a roughly 3:1 sex ratio; bachelor individuals are also observed.[14] In the mating season, males generally form herds and wander in search of mates. Females live with their offspring in herds, that very rarely include dominant males. Territorial males round up female herds that enter their territories and keep out the bachelors; mothers and juveniles may gather in nursery herds separate from harem and bachelor herds. After weaning, female juveniles stay with their mothers until the birth of their next calves, while males join bachelor groups.

A study of vigilance behaviour of herds revealed that individuals on the borders of herds tend to be more cautious, and vigilance decreases with group size. Group size and distance from roads and bushes were found to have major influence on vigilance, more among the grazing springbok than among their browsing counterparts. Adults were found to be more vigilant than juveniles, and males more vigilant than females. Springbok passing through bushes tend to be more vulnerable to predator attacks as they can not be easily alerted, and predators usually conceal themselves in bushes.[15] Another study calculated that the time spent in vigilance by springbok on the edges of herds is roughly double that spent by those in the centre and the open. Springbok were found to be more cautious in the late morning than at dawn or in the afternoon, and more at night than in the daytime. Rates and methods of vigilance were found to vary with the aim of lowering risk from predators.

During the rut, males establish territories, ranging from 10 to 70 hectares (25 to 173 acres), which they mark by urinating and depositing large piles of dung. Males in neighboring territories frequently fight for access to females, which they do by twisting and levering at each other with their horns, interspersed with stabbing attacks. Females roam the territories of different males. Outside of the rut, mixed-sex herds can range from as few as three to as many as 180 individuals, while all-male bachelor herds are of typically no more than 50 individuals. Harem and nursery herds are much smaller, typically including no more than 10 individuals.

In earlier times, when large populations of springbok roamed the Kalahari desert and Karoo, millions of migrating springbok formed herds hundreds of km long that could take several days to pass a town. These mass treks, known as trekbokking in Afrikaans, took place during long periods of drought. Herds could efficiently retrace their paths to their territories after long migrations. Trekbokking is still observed occasionally in Botswana, though on a much smaller scale than earlier.

Springbok often go into bouts of repeated high leaps of up to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) into the air – a practice known as pronking (derived from the Afrikaans pronk, "to show off") or stotting. In pronking, the springbok performs multiple leaps into the air in a stiff-legged posture, with the back bowed and the white flap lifted. When the male shows off his strength to attract a mate, or to ward off predators, he starts off in a stiff-legged trot, leaping into the air with an arched back every few paces and lifting the flap along his back. Lifting the flap causes the long white hairs under the tail to stand up in a conspicuous fan shape, which in turn emits a strong scent of sweat.[3] Although the exact cause of this behaviour is unknown, springbok exhibit this activity when they are nervous or otherwise excited. The most accepted theory for pronking is that it is a method to raise alarm against a potential predator or confuse it, or to get a better view of a concealed predator; it may also be used for display.

Springbok are very fast antelopes, clocked at 88 km/h (55 mph). They generally tend to be ignored by carnivores unless they are breeding. Cheetahs, lions, leopards, spotted hyenas, wild dogs, caracals, crocodiles and pythons are major predators of the springbok. Southern African wildcats, black-backed jackals, Verreaux's Eagles, martial eagles, and tawny eagles target juveniles. Springbok are generally quiet animals, though they may make occasional low-pitched bellows as a greeting and high-pitched snorts when alarmed.

Diet

Springbok are primarily browsers and may switch to grazing occasionally; they feed on shrubs and young succulents (such as Lampranthus species) before they lignify. They prefer grasses such as Themeda triandra. Springbok can meet their water needs from the food they eat, and are able to survive without drinking water through dry season. In extreme cases, they do not drink any water over the course of their lives. Springbok may accomplish this by selecting flowers, seeds, and leaves of shrubs before dawn, when the food items are most succulent. In places such as Etosha National Park, springbok seek out water bodies where they are available. Springbok gather in the wet season and disperse during the dry season, unlike other African mammals.

Reference: Wikipedia

Photos: Male Springbok (Yathin S Krishnappa), Pronking (Yathin S Krishnappa), Springbok mother and newborn (Mike Cawood), Rangemap (Yathin S Krishnappa)