NAMES

TAXONOMY

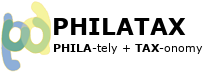

Nevis

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

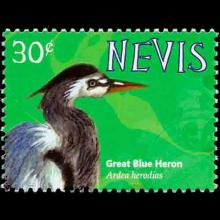

Dominica

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

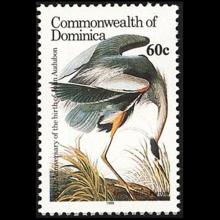

Barbados

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Nevis

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Dominica

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Barbados

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Nevis

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Dominica

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Barbados

Issued:

Stamp:

Ardea herodias

Disembarking the cruise ship near Cape Canaveral, FL, it sure felt good to walk on terra firma, and I was excited to wander around the area in the immediate proximity of the docked boat. My iPhone identified Manatee Sanctuary Park to be within reasonable walking distance, so I headed out. Although I didn't see any manatees, I did see a Great blue heron (Ardea herodias) and took a picture (the one at the top of the blue heron against a green grass background).

Genus species (Animalia): Ardea herodias

The great blue heron was one of the many species originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae. The scientific name comes from Latin ardea, and Ancient Greek erodios, both meaning "heron".

The great blue heron is replaced in the Old World by the very similar grey heron (Ardea cinerea), which differs in being somewhat smaller (90–98 cm (35–39 in)), with a pale gray neck and legs, lacking the browner colors that great blue heron has there. It forms a superspecies with this and also with the cocoi heron from South America, which differs in having more extensive black on the head, and a white breast and neck.

The five subspecies are:

- A. h. herodias Linnaeus, 1758, most of North America, except as below

- A. h. fannini Chapman, 1901, the Pacific Northwest from southern Alaska south to Washington; coastal

- A. h. wardi Ridgway, 1882, Kansas and Oklahoma to northern Florida, sightings in southeastern Georgia

- A. h. occidentalis Audubon, 1835, southern Florida, Caribbean islands, formerly known as a separate species, the great white heron

- A. h. cognata Bangs, 1903, Galápagos Islands

Description

It is the largest North American heron and, among all extant herons, it is surpassed only by the goliath heron (Ardea goliath) and the white-bellied heron (Ardea insignis). It has head-to-tail length of 91–137 cm (36–54 in), a wingspan of 167–201 cm (66–79 in), a height of 115–138 cm (45–54 in), and a weight of 1.82–3.6 kg (4.0–7.9 lb). In British Columbia, adult males averaged 2.48 kg (5.5 lb) and adult females 2.11 kg (4.7 lb). In Nova Scotia and New England, adult herons of both sexes averaged 2.23 kg (4.9 lb), while in Oregon, both sexes averaged 2.09 kg (4.6 lb) Thus, great blue herons are roughly twice as heavy as great egrets (Ardea alba), although only slightly taller than them, but they can weigh about half as much as a large goliath heron. Notable features of great blue herons include slaty (gray with a slight azure blue) flight feathers, red-brown thighs, and a paired red-brown and black stripe up the flanks; the neck is rusty-gray, with black and white streaking down the front; the head is paler, with a nearly white face, and a pair of black or slate plumes runs from just above the eye to the back of the head. The feathers on the lower neck are long and plume-like; it also has plumes on the lower back at the start of the breeding season. The bill is dull yellowish, becoming orange briefly at the start of the breeding season, and the lower legs are gray, also becoming orangey at the start of the breeding season. Immature birds are duller in color, with a dull blackish-gray crown, and the flank pattern is only weakly defined; they have no plumes, and the bill is dull gray-yellow. Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 43–49.2 cm (16.9–19.4 in), the tail is 15.2–19.5 cm (6.0–7.7 in), the culmen is 12.3–15.2 cm (4.8–6.0 in), and the tarsus is 15.7–21 cm (6.2–8.3 in).

The heron's stride is around 22 cm (8.7 in), almost in a straight line. Two of the three front toes are generally closer together. In a track, the front toes, as well as the back, often show the small talons.

Distribution and habitat

The great blue heron is found throughout most of North America, as far north as Alaska and the southern Canadian provinces. However, they are only present year-round in parts of Canada which have warmer winters, including coastal British Columbia and parts of its interior such as the warmer Okanagan Valley, as well as most of the Maritime provinces of eastern Canada. The range extends south through Florida, Mexico, and the Caribbean to South America. Birds east of the Rocky Mountains in the northern part of their range are migratory and winter in Central America or northern South America. From the southern United States southwards, and on the Pacific coast, they are year-round residents. However, their hardiness is such that individuals often remain through cold northern winters, as well, so long as fish-bearing waters remain unfrozen (which may be the case only in flowing water such as streams, creeks, and rivers).

The great blue heron can adapt to almost any wetland habitat in its range. It may be found in numbers in fresh and saltwater marshes, mangrove swamps, flooded meadows, lake edges, or shorelines. It is quite adaptable and may be seen in heavily developed areas as long as they hold bodies of fish-bearing water.

Great blue herons rarely venture far from bodies of water, but are occasionally seen flying over upland areas. They usually nest in trees or bushes near water's edge, often on islands (which minimizes the potential for predation) or partially isolated spots.

Diet

The primary food for great blue heron is small fish, though it is also known to opportunistically feed on a wide range of shrimp, crabs, aquatic insects, rodents, and other small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and birds. Primary prey is variable based on availability and abundance. In Nova Scotia, 98% of the diet was flounders. In British Columbia, the primary prey species are sticklebacks, gunnels, sculpins, and perch. California herons were found to live mostly on sculpin, bass, perch, flounder, and top smelt. Nonpiscine prey is rarely quantitatively important, though one study in Idaho showed that from 24 to 40% of the diet was made up of voles.

Herons locate their food by sight and usually swallow it whole. They have been known to choke on prey that is too large. It is generally a solitary feeder. Individuals usually forage while standing in water, but also feed in fields or drop from the air, or a perch, into water. Mice are occasionally preyed on in upland areas far from the species' typical aquatic environment. Occasionally, loose feeding flocks form and may be beneficial since they are able to locate schools of fish more easily. As large wading birds, great blue herons are capable of feeding in deeper waters, thus are able to harvest from niche areas not open to most other heron species. Typically, the great blue heron feeds in shallow waters, usually less than 50 cm (20 in) deep, or at the water's edge during both the night and the day, but especially around dawn and dusk. The most commonly employed hunting technique of the species is wading slowly with its long legs through shallow water and quickly spearing fish or frogs with its long, sharp bill. Although usually ponderous in movements, the great blue heron is adaptable in its fishing methods. Feeding behaviors variably have consisted of standing in one place, probing, pecking, walking at slow speeds, moving quickly, flying short distances and alighting, hovering over water and picking up prey, diving headfirst into the water, alighting on water feet-first, jumping from perches feet-first, and swimming or floating on the surface of the water.

Breeding

This species usually breeds in colonies, in trees close to lakes or other wetlands. Adults generally return to the colony site after winter from December (in warmer climes such as California and Florida) to March (in cooler areas such as Canada). Usually, colonies include only great blue herons, though sometimes they nest alongside other species of herons. These groups are called a heronry (a more specific term than "rookery"). The size of these colonies may be large, ranging between five and 500 nests per colony, with an average around 160 nests per colony. A heronry is usually relatively close, usually within 4 to 5 km (2.5 to 3.1 mi), to ideal feeding spots. Heronry sites are usually difficult to reach on foot (e.g., islands, trees in swamps, high branches, etc.) to protect from potential mammalian predators. Trees of any type are used when available. When not, herons may nest on the ground, sagebrush, cacti, channel markers, artificial platforms, beaver mounds, and duck blinds. Other waterbirds (especially smaller herons) and, occasionally, even fish and mammal-eating raptors may nest amongst colonies. Although nests are often reused for many years and herons are socially monogamous within a single breeding season, individuals usually choose new mates each year. Males arrive at colonies first and settle on nests, where they court females; most males choose a different nest each year. Great blue herons build a bulky stick nest. Nests are usually around 50 cm (20 in) across when first constructed, but can grow to more than 120 cm (47 in) in width and 90 cm (35 in) deep with repeated use and additional construction. If the nest is abandoned or destroyed, the female may lay a replacement clutch. Reproduction is negatively affected by human disturbance, particularly during the beginning of nesting. Repeated human intrusion into nesting areas often results in nest failure, with abandonment of eggs or chicks. However, Vancouver B.C. Canada's Stanley Park has had a healthy colony for some years right near its main entrance and tennis courts adjacent to English Bay and not far from Lost Lagoon. The park's colony has had as many as 140 nests. The Stanley Park Colony can be observed at their interactive web cam at http://vancouver.ca/parks-recreation-culture/heron-cam.aspx

Predation

Predators of eggs and nestlings include turkey vultures (Cathartes aura), common ravens (Corvus corax), and American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos). Red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), American black bears (Ursus americanus), and raccoons (Procyon lotor) are known to take larger nestlings or fledglings and, in the latter predator, many eggs. Adult herons, due to their size, have few natural predators, but a few of the larger avian predators have been known to kill both young and adults, including bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) (the only predator known to attack great blue herons at every stage of their lifecycle from in the egg to adulthood), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) and, less frequently, great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) and Harris's hawks (Parabuteo unicinctus). An occasional adult or, more likely, an unsteady fledgling may be snatched by an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) or an American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus). Using its considerable size and dagger-like bill, a full-grown heron can be a formidable foe to a predator. In one instance, during an act of attempted predation by a golden eagle, a heron was able to mortally wound the eagle although it succumbed to injures sustained in the fight. When predation on an adult or chick occurs at a breeding colony, the colony can sometimes be abandoned by the other birds. The primary source of disturbance and breeding failures at heronries is human activities, mostly through human recreation or habitat destruction, as well as by egg-collectors and hunters.

In art

John James Audubon illustrates the great blue heron in Birds of America, Second Edition (published, London 1827–38) as Plate 161. The image was engraved and colored by Robert Havell's, London workshops. The original watercolor by Audubon was purchased by the New-York Historical Society, where it remains to this day (January 2009).

Reference: Wikipedia

Photo: P. Needle Top picture taken at Manatee Sanctuary Park, Cape Canaveral, Florida, May 2016.