NAMES

TAXONOMY

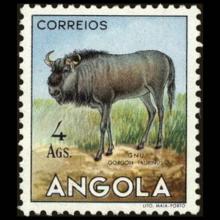

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Connochaetes taurinus

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Connochaetes taurinus

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Connochaetes taurinus

Genus species (Animalia): Connochaetes taurinus (Blue wildebeest)

The blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), also called the common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu, is a large antelope and one of the two species of wildebeest. It is placed in the genus Connochaetes and family Bovidae, and has a close taxonomic relationship with the black wildebeest. The blue wildebeest is known to have five subspecies. This broad-shouldered antelope has a muscular, front-heavy appearance, with a distinctive, robust muzzle. Young blue wildebeest are born tawny brown, and begin to take on their adult coloration at the age of 2 months. The adults' hues range from a deep slate or bluish-gray to light gray or even grayish-brown. Both sexes possess a pair of large curved horns.

The blue wildebeest is an herbivore, feeding primarily on short grasses. It forms herds which move about in loose aggregations, the animals being fast runners and extremely wary. The mating season begins at the end of the rainy season and a single calf is usually born after a gestational period of about 8.5 months. The calf remains with its mother for 8 months, after which it joins a juvenile herd. Blue wildebeest are found in short-grass plains bordering bush-covered acacia savannas in southern and eastern Africa, thriving in areas that are neither too wet nor too arid. Three African populations of blue wildebeest take part in a long-distance migration, timed to coincide with the annual pattern of rainfall and grass growth on the short-grass plains where they can find the nutrient-rich forage necessary for lactation and calf growth.

The blue wildebeest is native to Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Today, it is extinct in Malawi, but has been successfully reintroduced in Namibia. The southern limit of the blue wildebeest range is the Orange River, while the western limit is bounded by Lake Victoria and Mount Kenya. The blue wildebeest is widespread and is being introduced into private game farms, reserves, and conservancies. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources rates the blue wildebeest as being of least concern. The population has been estimated to be around 1.5 million, and the population trend is stable.

Taxonomy and naming

The blue wildebeest was first described in 1823 by English naturalist William John Burchell, who gave it the scientific name Connochaetes taurinus. It shares the genus Connochaetes with the black wildebeest (C. gnou), and is placed in the family Bovidae, ruminant animals with cloven hooves. The generic name Connochaetes derives from the Greek words κόννος, kónnos, "beard", and χαίτη, khaítē, "flowing hair", "mane". The specific name taurinus originates from the Greek word tauros, which means a bull or bullock. The common name "blue wildebeest" refers to the conspicuous, silvery-blue sheen of the coat, while the alternative name "gnu" originates from the name for these animals used by the Khoikhoi people, a native pastoralist people of southwestern Africa.

Though the blue and black wildebeest are currently classified in the same genus, the former was previously placed in a separate genus, Gorgon. In a study of the mitotic chromosomes and mtDNA, which was undertaken to understand more of the evolutionary relationships between the two species, the two were found to have a close phylogenetic relationship and had diverged about a million years ago.

Description

The blue wildebeest exhibits sexual dimorphism, with males being larger and darker than females. The blue wildebeest is typically 170–250 cm (67–98 in) in head-and-body length. The average height of the species is 115–151 cm (45–59 in). Males typically weigh 170 to 410 kg (370 to 900 lb) and females weigh 140 to 260 kg (310 to 570 lb). A characteristic feature is the long, black tail, which is around 60–100 cm (24–39 in) in length. All features and markings of this species are bilaterally symmetrical for both sexes. The average life span is 20 years in captivity. The oldest known captive individual lived for 24.3 years. The age that blue wildebeest live to in the wild is debatable.

Blue wildebeest have one of the most efficient locomotor muscles in terms of energy used for mechanical work and wasted as heat, with 62.6% of energy being converted into movement and the remainder in heat. They can travel up to 80 km (50 mi) in 5 days without drinking water, with average temperatures of 38 °C (100 °F) in peak times of the day.

Ecology ad behavior

The blue wildebeest is mostly active during the morning and the late afternoon, with the hottest hours of the day being spent in rest. These extremely agile and wary animals can run at speeds up to 80 km/h (50 mph), waving their tails and tossing their heads. An analysis of the activity of blue wildebeest at the Serengeti National Park showed that the animals devoted over half of their total time to rest, 33% to grazing, 12% to moving about (mostly walking), and a little to social interactions. However, variations existed among different age and sex groups.

The wildebeest usually rest close to others of their kind and move about in loose aggregations. Males form bachelor herds, and these can be distinguished from juvenile groups by the lower amount of activity and the spacing between the animals. Around 90% of the male calves join the bachelor herds before the next mating season. Bulls become territorial at the age of four or five years, and become very noisy (most notably in the western white-bearded wildebeest) and active. The bulls tolerate being close to each other and one square kilometre (0.39 sq mi) of plain can accommodate 270 bulls. Most territories are of a temporary nature and fewer than half of the male population hold permanent territories. In general, blue wildebeest rest in groups of a few to thousands at night, with a minimum distance of 1–2 m (3–7 ft) between individuals (though mothers and calves may remain in contact). They are a major prey item for lions, cheetahs, leopards, African wild dogs, hyenas, and Nile crocodiles.

Female calves will stay with their mothers and other related females of the herd throughout their lives. Female individuals in a herd are from a wide range of ages, from yearlings to the oldest cow. During the wet season, the females generally lead the herd towards nutritious areas of grasses and areas where predators can be avoided. This is to ensure that newborn calves have the highest chance of survival as well as gaining the most nutritious milk.

Bulls mark the boundaries of their territories with heaps of dung, secretions from their scent glands, and certain behaviors. Body language used by a territorial male includes standing with an erect posture, profuse ground pawing, and horning, frequent defecation, rolling and bellowing, and the sound "ga-noo" being produced. When competing over territory, males grunt loudly, paw the ground, make thrusting motion with their horns, and perform other displays of aggression.

Diet

The blue wildebeest is a herbivore, feeding primarily on the short grasses which commonly grow on light, and alkaline soils that are found in savanna grasslands and on plains. The animal's broad mouth is adapted for eating large quantities of short grass and it feeds both during the day and night. When grass is scarce, it will also eat the foliage of shrubs and trees. Wildebeest commonly associate with plains zebras as the latter eat the upper, less nutritious grass canopy, exposing the lower, greener material which the wildebeest prefer. Whenever possible, the wildebeest likes to drink twice daily and due to its regular requirement for water, it usually inhabits moist grasslands and areas with available water sources. The blue wildebeest drinks 9 to 12 liters of water every one to two days. Despite this, it can also survive in the arid Kalahari desert, where it obtains sufficient water from melons and water-storing roots and tubers.

In a study of the dietary habits of the wildebeest, the animals were found to be feeding on the three dominant kinds of grass of the area, namely: Themeda triandra, Digitaria macroblephara, and Pennisetum mezianum. The time spent grazing increased by about 100% during the dry season. Though the choice of the diet remained the same in both the dry and the wet season, the animals were more selective during the latter.

Distribution and habitat

The blue wildebeest is native to Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, South Africa, Eswatini, and Angola. Today, it is extinct in Malawi, but has been successfully reintroduced into Namibia.

Blue wildebeest are mainly found in short-grass plains bordering bush-covered acacia savannas in southern and eastern Africa, thriving in areas that are neither too wet nor too arid. They can be found in habitats that vary from overgrazed areas with dense bush to open woodland floodplains. Trees such as Brachystegia and Combretum spp. are common in these areas. Blue wildebeest can tolerate arid regions as long as a potable water supply is available, normally within about 15–25 km (9.3–15.5 mi) distance. The southern limit of the blue wildebeest stops at the Orange River, while the western limit is bounded by Lake Victoria and Mount Kenya. The range does not include montane or temperate grasslands. These wildebeest are rarely found at altitudes over 1,800–2,100 m (5,900–6,900 ft). With the exception of a small population of Cookson's wildebeest that occurs in the Luangwa Valley (Zambia), the wildebeest is absent in the wetter parts of the southern savanna country, and particularly is not present in miombo woodlands.

Three African populations of blue wildebeest take part in long-distance migrations, timed to coincide with the annual pattern of rainfall and grass growth on the short-grass plains, where they can find the nutrient-rich forage necessary for lactation and calf growth. The timing of the migration in both directions can vary considerably from year to year. At the end of the rainy season, they migrate to dry-season areas in response to a lack of drinking water. When the rainy season begins again a few months later, the animals trek back to their wet-season range. These movements and access to nutrient-rich forage for reproduction allow migratory wildebeest populations to grow to much larger numbers than resident populations. Many long-distance migratory populations of wildebeest existed 100 years ago, but currently, all but three migrations (Serengeti, Tarangire, and Kafue) have been disrupted, cut off, and lost.

Threats and conservation

Major human-related factors affecting populations include large-scale deforestation, the drying up of water sources, the expansion of settlements and poaching. Diseases of domestic cattle such as sleeping sickness can be transmitted to the animals and take their toll. The erection of fences that interrupt traditional migratory routes between wet and dry-season ranges have resulted in mass death events when the animals become cut off from water sources and the areas of better grazing they are seeking during droughts. A study of the factors influencing wildebeest populations in the Maasai Mara ecosystem revealed that the populations had undergone a drastic decline of around 80% from about 119,000 individuals in 1977 to around 22,000 twenty years later. The major cause of this was thought to be the expansion of agriculture, which led to the loss of wet-season grazing and the traditional calving and breeding ranges. Similarly, drastic declines have recently occurred in the Tarangire wildebeest migration.

The total number of blue wildebeest is estimated to be around 100,000. The population trend overall is unstable and the numbers in the Serengeti National Park (Tanzania) have increased to about 1,300,000. The population density ranges from 0.15/km2 in Hwange and Etosha National Parks to 35/km2 in Ngorongoro Crater and Serengeti National Park, where they are most plentiful. Blue wildebeest have also been introduced into a number of private game farms, reserves, and conservancy areas. For these reasons, the International Union for Conservation of Nature rates the blue wildebeest as being of least concern. However, the numbers of the eastern white-bearded wildebeest (C. t. albojubatus) have seen a steep decline to a current level of probably 6,000 to 8,000 animals, and this is causing some concern. The population of other subspecies are including; 150,000 in common wildebeest (C. t. taurinus), 5,000~75,000 in Nyassaland wildebeest (C. t. johnstoni), 5,000~10,000 in Cookson's wildebeest (C. t. cooksoni).

Relationships with humans

As one of the major herbivores of southern and eastern Africa, the blue wildebeest is one of the animals that draw tourists to the area to observe big game, and as such, it is of major economic importance to the region. Traditionally, blue wildebeest have been hunted for their hides and meat, the skin making good-quality leather, though the flesh is coarse, dry, and rather tough.

However, blue wildebeest can also affect human beings negatively. They can compete with domestic livestock for grazing and water and can transmit fatal diseases like rinderpest to cattle and cause epidemics among animals. They can also spread ticks, lungworms, tapeworms, flies, and paramphistome flukes.

An ancient carved slab of slate depicting an animal very similar to the blue wildebeest has been discovered. Dating back to around 3000 BC, it was found in Hierakonopolis (Nekhen), which used to be the religious and political capital of Upper Egypt at that time. This may be evidence that the animal used to occur in North Africa and was associated with the ancient Egyptians.

Reference: Wikipedia

Photos: Blue wildebeest (Muhammad Mahdi Karim), Female wildebeest and calf (Charles J. Sharp), Blue wildebeest migration (Serengeti Park Tanzania), range map (Cephas)