NAMES

TAXONOMY

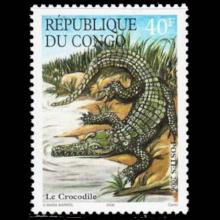

Republic of the Congo

Issued:

Stamp:

Crocodylus niloticus

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Crocodylus niloticus

Republic of the Congo

Issued:

Stamp:

Crocodylus niloticus

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Crocodylus niloticus

Republic of the Congo

Issued:

Stamp:

Crocodylus niloticus

Angola

Issued:

Stamp:

Crocodylus niloticus

Genus species: Crocodylus niloticus

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) is a large crocodilian native to freshwater habitats in Africa, where it is present in 26 countries. It is widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, occurring mostly in the eastern, southern, and central regions of the continent, and lives in different types of aquatic environments such as lakes, rivers, swamps, and marshlands. Although capable of living in saline environments, this species is rarely found in saltwater, but occasionally inhabits deltas and brackish lakes. The range of this species once stretched northward throughout the Nile River, as far north as the Nile Delta. Lake Rudolf in Kenya has one of the largest undisturbed populations of Nile crocodiles. Generally, the adult male Nile crocodile is between 3.5 and 5 m (11 ft 6 in and 16 ft 5 in) in length and weighs 225 to 750 kg (500 to 1,650 lb). However, specimens exceeding 6.1 m (20 ft) in length and 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) in weight have been recorded. It is the largest freshwater predator in Africa, and may be considered the second-largest extant reptile in the world, after the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Size is sexually dimorphic, with females usually about 30% smaller than males. The crocodile has thick, scaly, heavily armored skin.

Nile crocodiles are opportunistic apex predators; a very aggressive crocodile, they are capable of taking almost any animal within their range. They are generalists, taking a variety of prey, with a diet consisting mostly of different species of fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals. As ambush predators, they can wait for hours, days, and even weeks for the suitable moment to attack. They are agile predators and wait for the opportunity for a prey item to come well within attack range. Even swift prey are not immune to attack. Like other crocodiles, Nile crocodiles have a powerful bite that is unique among all animals, and sharp, conical teeth that sink into flesh, allowing a grip that is almost impossible to loosen. They can apply high force for extended periods of time, a great advantage for holding down large prey underwater to drown.

Nile crocodiles are relatively social. They share basking spots and large food sources, such as schools of fish and big carcasses. Their strict hierarchy is determined by size. Large, old males are at the top of this hierarchy and have first access to food and the best basking spots. Crocodiles tend to respect this order; when it is infringed, the results are often violent and sometimes fatal. Like most other reptiles, Nile crocodiles lay eggs; these are guarded by the females and males, making the Nile crocodiles one of few reptile species whose males contribute to parental care. The hatchlings are also protected for a period of time, but hunt by themselves and are not fed by the parents.

The Nile crocodile is one of the most dangerous species of crocodile and is responsible for hundreds of human deaths every year. It is common and is not endangered, despite some regional declines or extirpations in Maghreb.

Etymology and naming

The binomial name Crocodylus niloticus is derived from the Greek κρόκη, kroke ("pebble"), δρῖλος, drilos ("worm"), referring to its rough skin; and niloticus, meaning "from the Nile River". The Nile crocodile is called timsah al-nil in Arabic, mamba in Swahili, garwe in Shona, ngwenya in Ndebele, ngwena in Venda, kwena in Sotho and Tswana, and tanin ha-yeor in Hebrew. It also sometimes referred to as the African crocodile, Ethiopian crocodile, and common crocodile.

Characteristics and physiology

Adult Nile crocodiles have a dark bronze colouration above, with faded blackish spots and stripes variably appearing across the back and a dingy off-yellow on the belly, although mud can often obscure the crocodile's actual color. The flanks, which are yellowish-green in color, have dark patches arranged in oblique stripes in highly variable patterns. Some variation occurs relative to environment; specimens from swift-flowing waters tend to be lighter in color than those dwelling in murkier lakes or swamps, which provides camouflage that suits their environment, an example of clinal variation. Nile crocodiles have green eyes. The colouration also helps to camouflage them; juveniles are grey, multicolored, or brown, with dark cross-bands on the tail and body. The underbelly of young crocodiles is yellowish green. As they mature, Nile crocodiles become darker and the cross-bands fade, especially those on the upper-body. A similar tendency in coloration change during maturation has been noted in most crocodile species.

Most morphological attributes of Nile crocodiles are typical of crocodilians as a whole. Like all crocodilians, for example, the Nile crocodile is a quadruped with four short, splayed legs, a long, powerful tail, a scaly hide with rows of ossified scutes running down its back and tail, and powerful, elongated jaws. Their skin has a number of poorly understood integumentary sense organs that may react to changes in water pressure, presumably allowing them to track prey movements in the water. The Nile crocodile has fewer osteoderms on the belly, which are much more conspicuous on some of the more modestly sized crocodilians. The species, however, also has small, oval osteoderms on the sides of the body, as well as the throat. The Nile crocodile shares with all crocodilians a nictitating membrane to protect the eyes and lachrymal glands to cleanse its eyes with tears. The nostrils, eyes, and ears are situated on the top of the head, so the rest of the body can remain concealed under water. They have a four-chambered heart, although modified for their ectothermic nature due to an elongated cardiac septum, physiologically similar to the heart of a bird, which is especially efficient at oxygenating their blood. As in all crocodilians, Nile crocodiles have exceptionally high levels of lactic acid in their blood, which allows them to sit motionless in water for up to 2 hours. Levels of lactic acid as high as they are in a crocodile would kill most vertebrates. However, exertion by crocodilians can lead to death due to increasing lactic acid to lethal levels, which in turn leads to failure of the animal's internal organs. This is rarely recorded in wild crocodiles, normally having been observed in cases where humans have mishandled crocodiles and put them through overly extended periods of physical struggling and stress

Skull and head morphology

The mouths of Nile crocodiles are filled with 64 to 68 sharply pointed, cone-shaped teeth (about a dozen less than alligators have). For most of a crocodile's life, broken teeth can be replaced. On each side of the mouth, five teeth are in the front of the upper jaw (premaxilla), 13 or 14 are in the rest of the upper jaw (maxilla), and 14 or 15 are on either side of the lower jaw (mandible). The enlarged fourth lower tooth fits into the notch on the upper jaw and is visible when the jaws are closed, as is the case with all true crocodiles. Hatchlings quickly lose a hardened piece of skin on the top of their mouths called the egg tooth, which they use to break through their eggshells at hatching. Among crocodilians, the Nile crocodile possesses a relatively long snout, which is about 1.6 to 2.0 times as long as broad at the level of the front corners of the eyes. As is the saltwater crocodile, the Nile crocodile is considered a species with medium-width snout relative to other extant crocodilian species.

In a search for the largest crocodilian skulls in museums, the largest verifiable Nile crocodile skulls found were several housed in Arba Minch, Ethiopia, sourced from nearby Lake Chamo, which apparently included several specimens with a skull length more than 65 cm (26 in), with the largest one being 68.6 cm (27.0 in) in length with a mandibular length of 87 cm (34 in). Nile crocodiles with skulls this size are likely to measure in the range of 5.4 to 5.6 m (17 ft 9 in to 18 ft 4 in), which is also the length of the animals according to the museum where they were found. However, larger skulls may exist, as this study largely focused on crocodilians from Asia. The detached head of an exceptionally large Nile crocodile (killed in 1968 and measuring 5.87 m (19 ft 3 in) in length) was found to have weighed 166 kg (366 lb), including the large tendons used to shut the jaw.

Biting force

The bite force exerted by an adult Nile crocodile has been shown by Brady Barr to measure 22 kN (5,000 lbf). However, the muscles responsible for opening the mouth are exceptionally weak, allowing a person to easily hold them shut, and even larger crocodiles can be brought under control by the use of duct tape to bind the jaws together. The broadest snouted modern crocodilians are alligators and larger caimans. For example, a 3.9 m (12 ft 10 in) black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) was found to have a notably broader and heavier skull than that of a Nile crocodile measuring 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in). However, despite their robust skulls, alligators and caimans appear to be proportionately equal in biting force to true crocodiles, as the muscular tendons used to shut the jaws are similar in proportional size. Only the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) (and perhaps some of the few very thin-snouted crocodilians) is likely to have noticeably diminished bite force compared to other living species due to its exceptionally narrow, fragile snout. More or less, the size of the tendons used to impart bite force increases with body size and the larger the crocodilian gets, the stronger its bite is likely to be. Therefore, a male saltwater crocodile, which had attained a length around 4.59 m (15 ft 1 in), was found to have the most powerful biting force ever tested in a lab setting for any type of animal.

Size

The Nile crocodile is the largest crocodilian in Africa, and is generally considered the second-largest crocodilian after the saltwater crocodile. Typical size has been reported to be as much as 4.5 to 5.5 m (14 ft 9 in to 18 ft 1 in), but this is excessive for actual average size per most studies and represents the upper limit of sizes attained by the largest animals in a majority of populations. Alexander and Marais (2007) give the typical mature size as 2.8 to 3.5 m (9 ft 2 in to 11 ft 6 in); Garrick and Lang (1977) put it at from 3.0 to 4.5 m (9 ft 10 in to 14 ft 9 in). According to Cott (1961), the average length and weight of Nile crocodiles from Uganda and Zambia in breeding maturity was 3.16 m (10 ft 4 in) and 137.5 kg (303 lb). Per Graham (1968), the average length and weight of a large sample of adult crocodiles from Lake Turkana (formerly known as Lake Rudolf), Kenya was 3.66 m (12 ft 0 in) and body mass of 201.6 kg (444 lb). Similarly, adult crocodiles from Kruger National Park reportedly average 3.65 m (12 ft 0 in) in length. In comparison, the saltwater crocodile and gharial reportedly both average around 4 m (13 ft 1 in), so are about 30 cm (12 in) longer on average, and the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) may average about 3.75 m (12 ft 4 in), so may be slightly longer, as well. However, compared to the narrow-snouted, streamlined gharial and false gharial, the Nile crocodile is more robust and ranks second to the saltwater crocodile in total average body mass among living crocodilians, and is considered to be the second-largest extant reptile. The largest accurately measured male, shot near Mwanza, Tanzania, measured 6.45 m (21 ft 2 in) and weighed about 1,043–1,089 kg (2,300–2,400 lb). Another large male measuring 5.8 m (19 ft 0 in) in total length (Cott 1961) was among the largest Nile crocodiles ever recorded. It was estimated to weigh 1,082 kg (2,385 lb).

Behavior

Generally, Nile crocodiles are relatively inert creatures, as are most crocodilians and other large, cold-blooded creatures. More than half of the crocodiles observed by Cott (1961), if not disturbed, spent the hours from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. continuously basking with their jaws open if conditions were sunny. If their jaws are bound together in the extreme midday heat, Nile crocodiles may easily die from overheating. Although they can remain practically motionless for hours on end, whether basking or sitting in shallows, Nile crocodiles are said to be constantly aware of their surroundings and aware of the presence of other animals. However, mouth-gaping (while essential to thermoregulation) may also serve as a threat display to other crocodiles. For example, some specimens have been observed mouth-gaping at night, when overheating is not a risk. In Lake Turkana, crocodiles rarely bask at all through the day, unlike crocodiles from most other areas, for unknown reasons, usually sitting motionless partially exposed at the surface in shallows, with no apparent ill effects from the lack of basking on land.

In South Africa, Nile crocodiles are more easily observed in winter because of the extensive amount of time they spend basking at this time of year. More time is spent in water on overcast, rainy, or misty days. In the southern reaches of their range, as a response to dry, cool conditions that they cannot survive externally, crocodiles may dig and take refuge in tunnels and engage in aestivation. Pooley found in Royal Natal National Park that during aestivation, young crocodiles of 60 to 90 cm (24 to 35 in) total length would dig tunnels around 1.2 to 1.8 m (3 ft 11 in to 5 ft 11 in) in depth for most, with some tunnels measuring more than 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in), the longest there being 3.65 m (12 ft 0 in). Crocodiles in aestivation are lethargic, entering a state similar to animals that hibernate. Only the largest individuals engaging in aestivation leave the burrow to sun on the warmest days; otherwise, these crocodiles rarely left their burrows. Aestivation has been recorded from May to August.

Nile crocodiles usually dive for only a few minutes at a time, but can swim under water up to 30 minutes if threatened. If they remain fully inactive, they can hold their breath for up to 2 hours (which, as aforementioned, is due to the high levels of lactic acid in their blood). They have a rich vocal range and good hearing. Nile crocodiles normally crawl along on their bellies, but they can also "high walk" with their trunks raised above the ground. Smaller specimens can gallop, and even larger individuals are capable of occasional, surprising bursts of speed, briefly reaching up to 14 km/h (8.7 mph). They can swim much faster, moving their bodies and tails in a sinuous fashion, and they can sustain this form of movement much longer than on land, with a maximum known swimming speed of 30 to 35 km/h (19 to 22 mph).

Nile crocodiles have been widely known to have gastroliths in their stomachs, which are stones swallowed by animals for various purposes. Although this is clearly a deliberate behaviour for the species, the purpose is not definitively known. Gastroliths are not present in hatchlings, but increase quickly in presence within most crocodiles examined at 2–3.1 m (6 ft 7 in – 10 ft 2 in) and yet normally become extremely rare again in very large specimens, meaning that some animals may eventually expel them. However, large specimens can have a large number of gastroliths. One crocodile measuring 3.84 m (12 ft 7 in) and weighing 239 kg (527 lb) had 5.1 kg (11 lb) of stones in its stomach, perhaps a record gastrolith weight for a crocodile. Specimens shot near Mpondwe on the Semliki River had gastroliths in their stomach despite being shot miles away from any sources for the stones; the same holds true for specimens from Kafue Flats, Upper Zambesi and Bangweulu Swamp, all of which often had stones inside them despite being nowhere near stony regions. Cott (1961) felt that gastroliths were most likely serving as ballast to provide stability and additional weight to sink in water, this bearing great probability over the theories that they assist in digestion and staving off hunger. However, Alderton (1998) stated that a study using radiology found that gastroliths were seen to internally aid the grinding of food during digestion for a small Nile crocodile.

Herodotus claimed that Nile crocodiles have a symbiotic relationship with a bird named the Trochilus which enter the crocodile's mouth and pick leeches feeding on the crocodile's blood. Guggisberg (1972) had seen examples of birds picking scraps of meat from the teeth of basking crocodiles (without entering the mouth) and prey from soil very near basking crocodiles, so felt it was not impossible that a bold, hungry bird may occasionally nearly enter a crocodile's mouth, but not likely as a habitual behavior. MacFarland and Reeder, reviewing the evidence in 1974, found that: "Extensive observations of Nile crocodiles in regular or occasional association with various species of potential cleaners (e.g. Plovers, Sandpipers, water dikkop) ... have resulted in only a few reports of sandpipers removing leeches from the mouth and gular scutes and snapping at insects along the reptile's body." Matching Herodotus' description.

Hunting and diet

Nile crocodiles are apex predators throughout their range. In the water, this species is an agile and rapid hunter relying on both movement and pressure sensors to catch any prey unfortunate enough to present itself inside or near the waterfront. Out of water, however, the Nile crocodile can only rely on its limbs, as it gallops on solid ground, to chase prey. No matter where they attack prey, this and other crocodilians take practically all of their food by ambush, needing to grab their prey in a matter of seconds to succeed. They have an ectothermic metabolism, so can survive for long periods between meals. However, for such large animals, their stomachs are relatively small, not much larger than a basketball in an average-sized adult, so as a rule, they are anything but voracious eaters. Young crocodiles feed more actively than their elders, according to studies in Uganda and Zambia. In general, at the smallest sizes (0.3–1 m (1 ft 0 in – 3 ft 3 in), Nile crocodiles were most likely to have full stomachs (17.4% full per Cott); adults at 3–4 m (9 ft 10 in – 13 ft 1 in) in length were most likely to have empty stomachs (20.2%). In the largest size range studied by Cott, 4–5 m (13 ft 1 in – 16 ft 5 in), they were the second most likely to either have full stomachs (10%) or empty stomachs (20%). Other studies have also shown a large number of adult Nile crocodiles with empty stomachs. For example, in Lake Turkana, Kenya, 48.4% of crocodiles had empty stomachs. The stomachs of brooding females are always empty, meaning that they can survive several months without food.

The Nile crocodile mostly hunts within the confines of waterways, attacking aquatic prey or terrestrial animals when they come to the water to drink or to cross. The crocodile mainly hunts land animals by almost fully submerging its body under water. Occasionally, a crocodile quietly surfaces so that only its eyes (to check positioning) and nostrils are visible, and swims quietly and stealthily toward its mark. The attack is sudden and unpredictable. The crocodile lunges its body out of water and grasps its prey. On other occasions, more of its head and upper body is visible, especially when the terrestrial prey animal is on higher ground, to get a sense of the direction of the prey item at the top of an embankment or on a tree branch. Crocodile teeth are not used for tearing up flesh, but to sink deep into it and hold on to the prey item. The immense bite force, which may be as high as 5,000 lbf (22,000 N) in large adults, ensures that the prey item cannot escape the grip. Prey taken is often much smaller than the crocodile itself, and such prey can be overpowered and swallowed with ease. When it comes to larger prey, success depends on the crocodile's body power and weight to pull the prey item back into the water, where it is either drowned or killed by sudden thrashes of the head or by tearing it into pieces with the help of other crocodiles.

Subadult and smaller adult Nile crocodiles use their bodies and tails to herd groups of fish toward a bank, and eat them with quick sideways jerks of their heads. Some crocodiles of the species may habitually use their tails to sweep terrestrial prey off balance, sometimes forcing the prey specimen into the water, where it can be more easily drowned. They also cooperate, blocking migrating fish by forming a semicircle across the river. The most dominant crocodile eats first. Their ability to lie concealed with most of their bodies under water, combined with their speed over short distances, makes them effective opportunistic hunters of larger prey. They grab such prey in their powerful jaws, drag it into the water, and hold it underneath until it drowns. They also scavenge or steal kills from other predators, such as lions and leopards (Panthera pardus). Groups of Nile crocodiles may travel hundreds of meters from a waterway to feast on a carcass. They also feed on dead hippopotamuses (Hippopotamus amphibius) as a group (sometimes including three or four dozen crocodiles), tolerating each other. Much of the food from crocodile stomachs may come from scavenging carrion, and the crocodiles could be viewed as performing a similar function at times as do vultures or hyenas on land. Once their prey is dead, they rip off and swallow chunks of flesh. When groups are sharing a kill, they use each other for leverage, biting down hard and then twisting their bodies to tear off large pieces of meat in a "death roll". They may also get the necessary leverage by lodging their prey under branches or stones, before rolling and ripping.

The Nile crocodile possesses unique predation behavior characterized by the ability of preying both within water, where it is best adapted, and out of it, which often results in unpredictable attacks on almost any other animal up to twice its size. Most hunting on land is done at night by lying in ambush near forest trails or roadsides, up to 50 m (170 ft) from the water's edge. Since their speed and agility on land is rather outmatched by most terrestrial animals, they must use obscuring vegetation or terrain to have a chance of succeeding during land-based hunts. In one case, an adult crocodile charged from the water up a bank to kill a bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus) and instead of dragging it into the water, was observed to pull the kill further on land into the cover of the bush. Two subadult crocodiles were once seen carrying the carcass of a nyala (Tragelaphus angasii) across land in unison. In South Africa, a game warden far from water sources in a savannah-scrub area reported that he saw a crocodile jump up and grab a donkey by the neck and then drag the prey off. Small carnivores are readily taken opportunistically, including African clawless otters (Aonyx capensis).

Reference: Wikipedia

Photo: Dewet, Andrejs Medenis, fascinatingafrica.com