NAMES

TAXONOMY

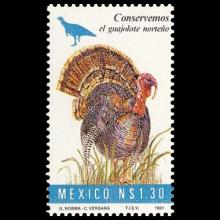

Mexico

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

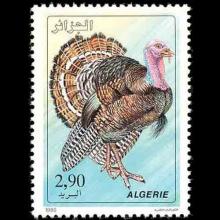

Algeria

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

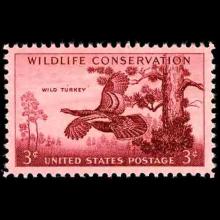

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

Mexico

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

Algeria

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

Mexico

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

Algeria

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Meleagris gallopavo

Link (in a new tab) to recordings of: Meleagris gallopavo (Wild turkey) at https://xeno-canto.org/

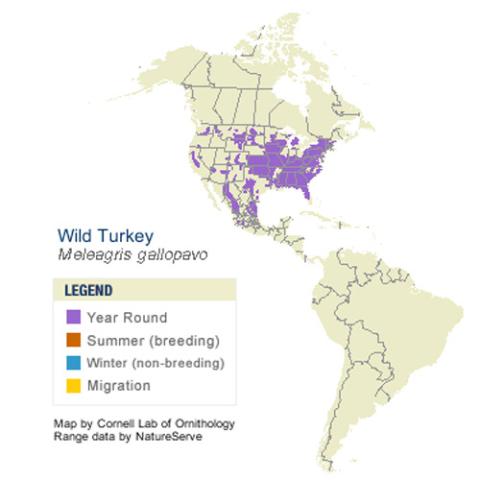

Genus species (Animalia): Meleagris gallopavo

The Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) and the Muscovy Duck (Cairina moschata) are the only two domesticated birds native to the New World.

In the early 1500s, European explorers brought home Wild Turkeys from Mexico, where native people had domesticated the birds centuries earlier. Turkeys quickly became popular on European menus thanks to their large size and rich taste from their diet of wild nuts. Later, when English colonists settled on the Atlantic Coast, they brought domesticated turkeys with them.

The English name of the bird may be a holdover from early shipping routes that passed through the country of Turkey on their way to delivering the birds to European markets.

Male Wild Turkeys provide no parental care. Newly hatched chicks follow the female, who feeds them for a few days until they learn to find food on their own. As the chicks grow, they band into groups composed of several hens and their broods. Winter groups sometimes exceed 200 turkeys.

As Wild Turkey numbers dwindled through the early twentieth century, people began to look for ways to reintroduce this valuable game bird. Initially they tried releasing farm turkeys into the wild but those birds didn’t survive. In the 1940s, people began catching wild birds and transporting them to other areas. Such transplantations allowed Wild Turkeys to spread to all of the lower 48 states (plus Hawaii) and parts of southern Canada.

Because of their large size, compact bones, and long-standing popularity as a dinner item, turkeys have a better known fossil record than most other birds. Turkey fossils have been unearthed across the southern United States and Mexico, some of them dating from more than 5 million years ago.

When they need to, Turkeys can swim by tucking their wings in close, spreading their tails, and kicking.

Reference: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Photos: ©P. Needle, 2017