NAMES

TAXONOMY

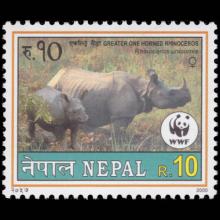

Nepal

Issued:

Stamp:

Rhinoceros unicornis

Nepal

Issued:

Stamp:

Rhinoceros unicornis

Nepal

Issued:

Stamp:

Rhinoceros unicornis

Genus species (Animalia): Rhinoceros unicornis

The Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), also known as the greater one-horned rhinoceros, great Indian rhinoceros, or Indian rhino for short, is a rhinoceros species native to the Indian subcontinent. It is the second largest extant species of rhinoceros, with adult males weighing 2.07–2.2 tonnes and adult females 1.6 tonnes. The skin is thick and is grey-brown in color with pinkish skin folds. They have a single horn on their snout that grows to a maximum of 57.2 cm (22.5 in). Their upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps, and aside from the eyelashes, ear fringes and tail brush, Indian rhinoceroses are nearly hairless.

The Indian rhinoceros is a largely solitary animal, only associating in the breeding season and when rearing calves. They are grazers, and their diet is mainly grass, but may also include twigs, leaves, branches, shrubs, flowers, fruits, and aquatic plants. Females give birth to a single calf after a gestation of 15.7 months; the birth interval is 34 to 51 months. Captive individuals can live up to 47 years. The Indian rhinoceros is susceptible to diseases such as anthrax, and those caused by parasites such as leeches, ticks, and nematodes.

It is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, as populations are fragmented and restricted to less than 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi). As of August 2018, the global population was estimated to comprise 3,588 individuals. Indian rhinos once ranged throughout the entire stretch of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, but excessive hunting and agricultural development reduced its range drastically to 11 sites in northern India and southern Nepal. In the early 1990s, between 1,870 and 1,895 Indian rhinos were estimated to have been alive. Since then, numbers have increased due to conservation measures taken by the government. However, poaching remains a continuous threat.

Taxonomy

Rhinoceros unicornis was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 who described a rhinoceros with one horn. As type locality, he indicated Africa and India. He described two species in India, the other being Rhinoceros bicornis, and stated that the Indian species had two horns, while the African species had only one.

The Indian rhinoceros is a single species. Several specimens were described since the end of the 18th century under different scientific names, which are all considered synonyms of Rhinoceros unicornis today:

- R. indicus by Cuvier, 1817

- R. asiaticus by Blumenbach, 1830

- R. stenocephalus by Gray, 1867

- R. jamrachi by Sclater, 1876

- R. bengalensis by Kourist, 1970

Etymology The generic name rhinoceros is derived through Latin from the Ancient Greek: ῥινόκερως, which is composed of ῥινο- (rhino-, "of the nose") and κέρας (keras, "horn") with a horn on the nose. The name has been in use since the 14th century. The Latin word ūnicornis means "one-horned".

Characteristics

Indian rhinos have a thick grey-brown skin with pinkish skin folds and one horn on their snout. Their upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps. They have very little body hair, aside from eyelashes, ear fringes and tail brush. Bulls have huge neck folds. The skull is heavy with a basal length above 60 cm (24 in) and an occiput above 19 cm (7.5 in). The nasal horn is slightly back-curved with a base of about 18.5 cm (7.3 in) by 12 cm (4.7 in) that rapidly narrows until a smooth, even stem part begins about 55 mm (2.2 in) above base. In captive animals, the horn is frequently worn down to a thick knob.

The Indian rhino's single horn is present in both bulls and cows, but not on newborn calves. The horn is pure keratin, like human fingernails, and starts to show after about six years. In most adults, the horn reaches a length of about 25 cm (9.8 in), but has been recorded up to 57.2 cm (22.5 in) in length and 3.051 kg (6.73 lb) in weight.

Among terrestrial land mammals native to Asia, Indian rhinos are second in size only to the Asian elephant. They are also the second-largest living rhinoceros, behind only the white rhinoceros. Bulls have a head and body length of 368–380 cm (12.07–12.47 ft) with a shoulder height of 163–193 cm (5.35–6.33 ft), while cows have a head and body length of 310–340 cm (10.2–11.2 ft) and a shoulder height of 147–173 cm (4.82–5.68 ft). The bull, averaging about 2,070–2,200 kg (4,560–4,850 lb) is heavier than the cow, at an average of about 1,600 kg (3,530 lb).

The rich presence of blood vessels underneath the tissues in folds gives them the pinkish color. The folds in the skin increase the surface area and help in regulating the body temperature. The thick skin does not protect against bloodsucking Tabanus flies, leeches and ticks.

The largest individuals reportedly weigh up to 4,000 kg (8,820 lb).

Threats

Habitat degradation caused by human activities and climate change as well as the resulting increase in the floods has caused many Indian rhino deaths and has limited their ranging areas which is shrinking.

Serious declines in quality of habitat have occurred in some areas, due to severe invasion by alien plants into grasslands affecting some populations, and demonstrated reductions in the extent of grasslands and wetland habitats due to woodland encroachment and silting up of beels (swampy wetlands). Grazing by domestic livestock is another cause.

The Indian rhino species is inherently at risk because over 70% of its population occurs at a single site, Kaziranga National Park. Any catastrophic event such as disease, civil disorder, poaching, or habitat loss would have a devastating impact on the Indian rhino's status. However, small population of rhinos may be prone to inbreeding depression.

Poaching

Sport hunting became common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and was the main cause for the decline of Indian rhinoceros populations. Indian rhinos were hunted relentlessly and persistently. Reports from the mid-19th century claim that some British military officers shot more than 200 rhinos in Assam alone. By 1908, the population in Kaziranga National Park had decreased to around 12 individuals. In the early 1900s, the Indian rhinoceros was almost extinct. At present, poaching for the use of horn in traditional Chinese Medicine is one of the main threats that has led to decreases in several important populations. Poaching for the Indian rhino's horn became the single most important reason for the decline of the Indian rhinoceros after conservation measures were put in place from the beginning of the 20th century, when legal hunting ended. From 1980 to 1993, 692 rhinos were poached in India, including 41 rhinos in India's Laokhowa Wildlife Sanctuary in 1983, almost the entire population of the sanctuary. By the mid-1990s, the Indian rhinoceros had been extirpated in this sanctuary. Between 2000 and 2006, more than 150 rhinos were poached in Assam. Almost 100 rhinos were poached in India between 2013 and 2018.

In 1950, in Nepal the Chitwan's forest and grasslands extended over more than 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi) and were home to about 800 rhinos. When poor farmers from the mid-hills moved to the Chitwan Valley in search of arable land, the area was subsequently opened for settlement, and poaching of wildlife became rampant. The Chitwan population has repeatedly been jeopardized by poaching; in 2002 alone, poachers killed 37 animals to saw off and sell their valuable horns.

Conservation

The Indian rhinoceros is listed as vulnerable by the IUCN Red list, as of 2018. Globally, R. unicornis has been listed in CITES Appendix I since 1975. The Indian and Nepalese governments have taken major steps towards Indian rhinoceros conservation, especially with the help of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and other non-governmental organizations. In 1910, all rhino hunting in India became prohibited.

In 1957, the country's first conservation law ensured the protection of rhinos and their habitat. In 1959, Edward Pritchard Gee undertook a survey of the Chitwan Valley, and recommended the creation of a protected area north of the Rapti River and of a wildlife sanctuary south of the river for a trial period of 10 years. After his subsequent survey of Chitwan in 1963, he recommended extension of the sanctuary to the south. By the end of the 1960s, only 95 rhinos remained in the Chitwan Valley. The dramatic decline of the rhino population and the extent of poaching prompted the government to institute the Gaida Gasti – a rhino reconnaissance patrol of 130 armed men and a network of guard posts all over Chitwan. To prevent the extinction of rhinos, the Chitwan National Park was gazetted in December 1970, with borders delineated the following year and established in 1973, initially encompassing an area of 544 km2 (210 sq mi). To ensure the survival of rhinos in case of epidemics, animals were translocated annually from Chitwan to Bardia National Park and Shuklaphanta National Park since 1986. The Indian rhinoceros population living in Chitwan and Parsa National Parks was estimated at 608 mature individuals in 2015.