NAMES

TAXONOMY

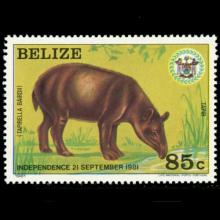

Belize

Issued:

Stamp:

Tapirus bairdii

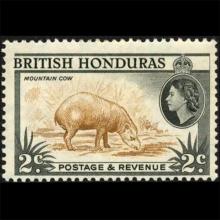

British Honduras

Issued:

Stamp:

Tapirus bairdii

Belize

Issued:

Stamp:

Tapirus bairdii

British Honduras

Issued:

Stamp:

Tapirus bairdii

Belize

Issued:

Stamp:

Tapirus bairdii

British Honduras

Issued:

Stamp:

Tapirus bairdii

Wildlife trade imperils species, even in protected areas

by Elizabeth Pennisi, Feb. 15, 2021

Wildlife trafficking is having a profound negative impact on biodiversity, a new analysis finds. Hunting and trapping to feed international and national trade networks threaten numerous species, the researchers report, even those living in protected areas. “This study adds to the growing body of evidence that commercial wildlife trade is a significant threat,” says Scott Roberton, a conservationist in charge of antitrafficking programs at the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Wildlife trafficking is big business, with analysts estimating it generates between $5 billion and $20 billion per year. It involves the capture or killing of tens of millions of individuals from thousands of species, and some 150 million families depend on eating wild animals or selling them for their livelihoods. And although some of this activity is legal, much is illegal.

For decades, many conservationists have said wildlife trafficking is driving some species to extinction. But others have argued that “trade can often be sustainable,” says conservation biologist David Edwards of the University of Sheffield.

To begin to evaluate that possibility, Edwards and his graduate student, Oscar Morton, as well as a number of colleagues, assembled 31 papers that examined wildlife populations in areas where hunting and trapping occurred, as well as in areas where there was none. Overall, these papers chronicled the fates of individuals from 133 species: 452 mammals belonging to 99 species, 36 birds from 24 species, and 18 reptiles from 10 species.

The researchers then built models that helped them assess the impact that a variety of factors might be having on populations of these 133 species. The factors included how much trade there was in a species; whether it was desired for food, medicine, or some other purpose; and how far the species lived from human settlements and potential markets. They also looked at whether the species lived in a protected or unprotected area.

Overall, the team found the studied species were less abundant if they lived in areas that lacked protection. Without game wardens to enforce quotas or boundaries, for example, populations declined by 65%, the researchers report today in Nature Ecology & Evolution. In areas where animals were traded for food (bushmeat), there was almost a 60% decline in the populations. And in places where animals such as songbirds were being trapped for sale as pets, population declines could reach 73%. In general, “the closer to human settlements the study sites were, the greater the decline in abundance,” Edwards says. In 83 of the 506 examples they studied, the hunted species had disappeared entirely from the study area.

But even in protected areas, declines were dramatic, with populations dropping by 39%.

The study’s bottom line, Edwards says, is that “wildlife trade drives species to decline, often severely, including within protected areas. … We checked a whole range of different methods and always found these large significant declines.”

“To my knowledge, this is the first time that a group of scientists has attempted to synthesize the existing information on what the wildlife trade is doing to wild populations,” says David Wilcove, a conservation biologist at Princeton University who was not involved with the work. But the 133 species it evaluated are just the tip of the iceberg, he adds. “There are thousands of species being traded for which we haven’t the slightest clue as to what it’s doing to their populations in the wild.”

The analysis also highlights a gaping hole in wildlife research. Most of the 31 studies focused on mammals, and there were none about invertebrates, amphibians, or plants like orchids and cacti—all organisms traded by the millions. In addition, there were only four studies in Asia, “a big hot spot for wildlife trade,” says Maria Bager Olsen, a conservation biologist at the Natural History Museum of Denmark. Such gaps emphasize “the need for a bigger diversification in study areas,” she says.

Steve Broad, executive director of TRAFFIC, an organization working toward sustainable wildlife trade, is cautious about the conclusions. He wonders, for example, whether there might be other reasons—such as habitat degradation or loss—for the species declines seen in some areas and agrees that conservation efforts would benefit from a better understanding of such issues. “It will be interesting,” he says, “to dig deeper.”

Reference: www.sciencemag.org

Genus species (Animalia): Tapirus bairdii

Baird's tapir (Tapirus bairdii), also known as the Central American tapir, is a species of tapir native to Mexico, Central America, and northwestern South America. It is the largest of the three species of tapir native to the Americas, as well as the largest native land mammal in both Central and South America.

Names

Baird's tapir is named for the American naturalist Spencer Fullerton Baird, who traveled to Mexico in 1843 and observed the animals. However, the species was first documented by another American naturalist, W. T. White.

Like the other American tapirs (the mountain tapir, the South American tapir, and the little black tapir), the Baird's tapir is commonly called danta by people in all areas. In the regions around Oaxaca and Veracruz, it is referred to as the anteburro. Panamanians, and Colombians call it macho de monte, and in Belize, where the Baird's tapir is the national animal, it is known as the mountain cow.

In Mexico, it is called tzemen in Tzeltal; in Lacandon, it is called cash-i-tzimin, meaning "jungle horse" and in Tojolab'al it is called niguanchan, meaning "big animal". In Panama, the Kunas people call the Baird's tapir moli in their colloquial language (Tule kaya), oloalikinyalilele, oloswikinyaliler, or oloalikinyappi in their political language (Sakla kaya), and ekwirmakka or ekwilamakkatola in their spiritual language (Suar mimmi kaya).

Description

Baird's tapir has a distinctive cream-colored marking on its face, throat, and tips of its ears, with a dark spot on each cheek, behind and below the eye. The rest of its hair is dark brown or grayish brown. Baird's tapirs average 2 m (6.6 ft) in length, but can range between 1.8 and 2.5 m (5.9 and 8.2 ft), not counting a stubby, vestigal tail of 5–13 cm (2.0–5.1 in), and 73–120 cm (2.40–3.94 ft) in height. Body mass in adults can range from 150 to 400 kilograms (330 to 880 lb). Like the other species of tapirs, they have small, stubby tails and long, flexible proboscises. They have four toes on each front foot, and three toes on each back foot.

Lifecycle

The gestation period is about 400 days, after which one offspring is born. Multiple births are extremely rare, but in September 2020, a Baird's tapir in Boston's Franklin Park Zoo birthed twins. The babies, as with all species of tapir, have reddish-brown hair with white spots and stripes, a camouflage which affords them excellent protection in the dappled light of the forest. This pattern eventually fades into the adult coloration. For the first week of their lives, infant Baird's tapirs are hidden in secluded locations while their mothers forage for food, and return periodically to nurse them. Later, the young follow their mothers on feeding expeditions. At three weeks of age, the young are able to swim. Weaning occurs after one year, and sexual maturity is usually reached six to 12 months later. Baird's tapirs can live for over 30 years.

Behavior

Baird's tapir may be active at all hours, but is primarily nocturnal. It forages for leaves and fallen fruit, using well-worn tapir paths which zig-zag through the thick undergrowth of the forest. The animal usually stays close to water and enjoys swimming and wading – on especially hot days, individuals will rest in a watering hole for hours with only their heads above water.

It generally leads a solitary life, though feeding groups are not uncommon and individuals, especially those of different ages (young with their mothers, juveniles with adults) are often observed together. The animals communicate with one another through shrill whistles and squeaks.

The Baird's tapir has a symbiotic relationship with cleaner birds that remove ticks from its fur: the yellow-headed caracara (Milvago chimachima) and the black vulture (Coragyps atratus) have both been observed removing and eating ticks from tapirs. The tapirs often lie down for cleaning, and also present tick-infested areas to the cleaner birds by lifting limbs, and rolling from one side to the other.

Potential danger to humans

Attacks on humans are rare and normally in self-defense. In 2006, Carlos Manuel Rodríguez Echandi, the former Costa Rican Minister of Environment and Energy, was attacked and injured by a tapir after he followed it off the trail.

Due to their size, adults can be potentially dangerous to humans, and should not be approached if spotted in the wild. The animal is most likely to follow or chase a human for a bit, though they have been known to charge and gore humans on rare occasions.

Conservation

According to the IUCN, Baird's tapir is endangered. There are two main contributing factors in the decline of the species; poaching and habitat loss. Though in many areas, the animal is only hunted by a few humans, any loss of life is a serious blow to the tapir population, especially because their reproductive rate is so slow. Additionally, a study showed a small population of Baird's tapir in North American and Central American zoos had inbreeding and divergence from the wild population.

In Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Panama, hunting of the Baird's tapirs is illegal, but the laws protecting them are often unenforced. Furthermore, restrictions against hunting do not address the problem of deforestation. Therefore, many conservationists focus on environmental education and sustainable forestry to try to save the Baird's tapir and other rainforest species from extinction.

Predators

Due to its size, an adult Baird's tapir has very few natural predators. Only large adult American crocodiles (4 meters or 13 feet or more) and adult jaguars are capable of preying on tapirs, although even in these cases, the outcomes are unpredictable and often in the tapir's favor (as is evident on multiple tapirs documented in Corcovado National Park with large claw marks covering their hides). However, young may be preyed on by smaller crocodiles and pumas.

Reference: Wikipedia

Photos: japari-library.com, Bjørn Christian Tørrissen, Eric Kilby