NAMES

TAXONOMY

Canada

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

Romania

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

Canada

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

Romania

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

Canada

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

Romania

Issued:

Stamp:

Vulpes vulpes

Humans are disrupting predator diets

Eating our food could upset communities and ecosystems.

Predators living near people are getting up to half their food or even more from human sources, US researchers have discovered.

This could cause a cascade of problems, from human-carnivore conflict to ultimately upsetting predator-prey interactions, communities and ecosystems, they write in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In the animal kingdom, co-existence relies on managing space, time and resources to limit competition, an ecological concept known as “niche partitioning”, explain Philip Manlick and Jonathan Pauli from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Of these, they write that resource partitioning is arguably the most important, with critical implications for predator-dominated ecosystems. But they say its vulnerability to human activities is least understood, despite evidence that carnivores are “adaptable foragers”.

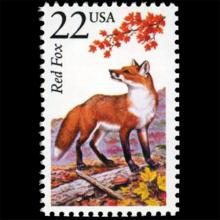

To address this, the pair investigated the diets of seven predator species, including bobcats (Lynx rufus), coyotes (Canis latrans), fishers (Pekania pennanti), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), martens (Martes americana) and grey wolves (Canis lupis) and the corresponding human footprint across the Great Lakes Region – an ideal target for the study.

“One of the most altered biomes on the planet, this region is notable for its recovered carnivore communities, high carnivore richness, and broad spectrum of human disturbance,” they write.

With help from other researchers and citizen scientist trappers, Pauli and Manlick amassed bone and hair samples from 684 carnivores across seven communities spanning pristine wilderness such as protected national parks to farms and urban areas including Albany, New York.

As food leaves different carbon signatures, isotopic analysis of bone samples can reveal what the animals ate. Human diets, for instance, are distinctively high in corn and sugar.

“Isotopes are relatively intuitive: you are what you eat,” says Manlick. “If you look at humans, we look like corn.” Prey leaves a different carbon signature, enabling the researchers to identify the proportion of human food in predator diets.

Results showed a “strong and consistent response to human disturbance”. More than 25% of the average predator diet comprised human foods in the most disrupted areas, although this also varied by species.

Hardcore carnivores like bobcats ate less human food compared to more generalist species such as coyotes, foxes, fishers and martens, which were getting more than 50% of their diet from human foods.

These top predators are globally the most abundant and diverse, the authors note, with vital ecological functions.

Their reliance on human food could increase their vulnerability to human attack, the researchers suggest, and create more conflicts between carnivores by increasing their overlap when competing for human food compared to prey.

It could also change how and when they hunt, impacting predator-prey dynamics and potentially the broader ecosystem, something Pauli suggests ecologists and conservation biologists need to further understand as humans continue their expansion across the planet. “When you change the landscape so dramatically in terms of one of the most important attributes of a species – their food – that has unknown consequences for the overall community structure.”

Genus species (Animalia): Vulpes vulpes

Vulpes vulpes (Red fox) females are called vixens, and young cubs are known as kits. Although the Arctic fox has a small native population in northern Scandinavia, while the corsac fox's range extends into European Russia, the red fox is the only fox native to Western Europe, and so is simply called "the fox" in colloquial British English. The word "fox" comes from Old English, which derived from Proto-Germanic *fuhsaz. Compare with West Frisian foks, Dutch vos, and German Fuchs. This, in turn, derives from Proto-Indo-European *puḱ- 'thick-haired; tail'. Compare to the Hindi pū̃ch 'tail', Tocharian B päkā 'tail; chowrie', and Lithuanian paustìs 'fur'. The bushy tail also forms the basis for the fox's Welsh name, llwynog, literally 'bushy', from llwyn 'bush'. Likewise, Portuguese: raposa from rabo 'tail', Lithuanian uodẽgis from uodegà 'tail', and Ojibwa waagosh from waa, which refers to the up and down "bounce" or flickering of an animal or its tail. The scientific term vulpes derives from the Latin word for fox, and gives the adjectives vulpine and vulpecular.

Description

The red fox has an elongated body and relatively short limbs. The tail, which is longer than half the body length (70 per cent of head and body length), is fluffy and reaches the ground when in a standing position. Their pupils are oval and vertically oriented. Nictitating membranes are present, but move only when the eyes are closed. The forepaws have five digits, while the hind feet have only four and lack dewclaws. They are very agile, being capable of jumping over 2-meter-high (6 ft 7 in) fences, and swim well. Vixens normally have four pairs of teats, though vixens with seven, nine, or ten teats are not uncommon. The testes of males are smaller than those of Arctic foxes. Their skulls are fairly narrow and elongated, with small braincases. Their canine teeth are relatively long. Sexual dimorphism of the skull is more pronounced than in corsac foxes, with female red foxes tending to have smaller skulls than males, with wider nasal regions and hard palates, as well as having larger canines. Their skulls are distinguished from those of dogs by their narrower muzzles, less crowded premolars, more slender canine teeth, and concave rather than convex profiles.

Behavior

Urban red foxes are most active at dusk and dawn, doing most of their hunting and scavenging at these times. It is uncommon to spot them during the day, but they can be caught sunbathing on roofs of houses or sheds. Foxes will often make their homes in hidden and undisturbed spots in urban areas as well as on the edges of a city, visiting at night for sustenance. While foxes will scavenge successfully in the city (and the foxes tend to eat anything that the humans eat) some urban residents will deliberately leave food out for the animals, finding them endearing. Doing this regularly can attract foxes to one's home; they can become accustomed to human presence, warming up to their providers by allowing themselves to be approached and in some cases even played with, particularly young cubs.

Reference: Wikipedia

Photo: pgcpsmess.wordpress.com