NAMES

TAXONOMY

FUNGI ID

THERAPEUTIC

Italy

Issued:

Stamp:

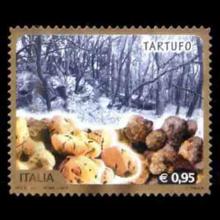

Tuber gibbosum

Italy

Issued:

Stamp:

Tuber gibbosum

Italy

Issued:

Stamp:

Tuber gibbosum

In Oregon, Truffles Are No Match for Wet Noses

by Nick Czap, Aug. 7, 2012

Redland, OR

THE forest air was cool and the light translucently green, sifted through the Douglas-fir canopy above and refracted by plumes of sword ferns that sprang from the forest floor. There was a muffled galumphing, a blur of golden fur, and then another, as Sasha and Ashleigh, two golden retrievers, bounded by off-leash in a kind of dog nirvana, followed closely by their owners, Kim Hickey and Erik Campen.

Recent graduates of NW Truffle Dogs, a school in Oregon City, Ore., the four were fast becoming adroit hunters of Oregon truffles, native fungi that are among the Pacific Northwest’s most prized delicacies. The dogs and their owners are also pioneers of a sort, foragers at the forefront of a movement that seeks to improve the reputation of Oregon truffles, and their value in the market, by changing the way they are harvested.

As Sasha and Ashleigh raced along, noses to the ground, in these woods, about 20 miles south of Portland, Ms. Hickey watched intently. But something in the dogs’ postures told her they were following the scent of an animal, the footfalls of a squirrel or a chipmunk.

“They’re crittering,” Ms. Hickey said.

Oregon is home to four known culinary truffles: Leucangium carthusianum, the Oregon black truffle; Tuber oregonense, the Oregon winter white; Tuber gibbosum, the Oregon spring white; and Kalapuya brunnea, the relatively rare Oregon brown truffle.

Harvesting the fungi, which grow beneath the forest’s mulch layer or several inches of soil, is labor intensive, a fact reflected in a retail price of about $400 a pound. Still, that is considerably less than the going rate for truffles from places like Alba, Italy, and Périgord, France, which this year commanded $4,000 and $1,600 a pound, respectively.

While European truffles have been harvested on a significant scale since the 19th century, Oregon’s truffle harvest is a relatively recent phenomenon. The industry had only just begun to germinate in 1977 when James Beard gave it a boost, declaring at a mushroom symposium that Oregon white truffles were as good as their Italian counterparts.

But the harvests in Europe and Oregon differ in another, significant respect. European foragers use dogs or pigs trained to sniff out ripe truffles, ensuring a crop of uniformly high quality; Italian law mandates the use of dogs. Most commercial foragers in Oregon harvest the fungi by raking, a method that gathers both mature and immature truffles. The problem is amplified when foragers try to beat competitors by raking for truffles progressively earlier in the growing season.

Charles Lefevre — whose company, New World Truffieres, in Eugene, Ore., specializes in truffle cultivation — said he thought that the resulting crop neither consistently conveyed the full culinary potential of Oregon truffles, nor commanded the prices that it could.

To help fix that, in 2006 Mr. Lefevre, who holds a Ph.D. in forest mycology, and his wife, Leslie Scott, founded the Oregon Truffle Festival, an annual event that seeks to improve the reputation of Oregon truffles by promoting the use of truffle dogs.

In 2009, Mr. Lefevre was among the authors of a white paper saying that industry oversight to ensure the use of dogs, combined with cultivation efforts and careful management of the truffle habitat, could raise the value of Oregon’s crop (worth $300,000 to harvesters at the time) a hundredfold by 2030, and benefit the region’s economy through increased sales, exports and culinary tourism.

Elizabeth Kalik, a former trainer of search-and-rescue dogs in Oregon City, read an article in the dog enthusiast magazine Bark in which Mr. Lefevre described the need for truffle dogs. Intrigued by the prospect of a new outlet for her canine expertise, she tracked him down and promptly trained her dogs, a Newfoundland and two Beaucerons, to home in on the scent of truffles.

She and a former search-and-rescue colleague, Kelly Slocum, founded NW Truffle Dogs in 2010. To date, the school has trained 46 dogs — including a papillon and a pit bull — as well as their owners, who must learn to detect the changes in a dog’s behavior and posture as it closes in on its quarry. Truffles are a food, after all, and some dogs will eagerly gobble them up if not watched carefully. Oregon black truffles exude an aroma reminiscent of pineapple and dark chocolate, while the white and brown varieties evoke a mélange of spices, sulfur and ripe cheese. For dogs, whose noses are extraordinarily sensitive, tracking these aromas to their source is relatively straightforward.

“Scent training is one of the easiest things you can do with a dog, because of the natural proclivity,” Ms. Kalik said. But before any instruction, she and Ms. Slocum evaluate each dog’s suitability for truffling, which requires a good degree of fitness, an ability to think independently and focus on a task for hours, and a tolerance for occasionally cold, damp conditions.

“You can train any breed,” said Ms. Kalik, but breeds like Labrador and golden retrievers, which make good pets and good working dogs, are “a happy medium.” To date, all of the school’s graduates, including Ms. Hickey and Mr. Campen, have been amateur foragers. Ms. Kalik and Ms. Slocum encourage their students to spread the word by joining their local mycological society and taking their dogs on group foraging trips, where they can show their abilities. While Ms. Hickey and Mr. Campen have yet to join such a club, they are happily finding uses for the fruits, or fungi, of their labor. Ms. Hickey’s current favorite is truffled potato gratin. During the foray through the woods, after zigzagging through the sword ferns for nearly an hour, Sasha came to an abrupt halt, sniffed the air, and began to backtrack, her zigs and zags becoming smaller and more precise. Moments later, the dog put her snout to the ground, her tail wagging in a slow, peculiar way that whispered “truffle.”

Mr. Campen scampered over, knelt beside her and began scratching at the soil with a soup spoon. With a whoop, he held aloft an Oregon black truffle the size of a table tennis ball — the first of several. It was earthy, fruity and, owing to the nose that found it, unquestionably, aromatically and exquisitely ripe.

Genus species (Fungi): Tuber gibbosum

Tuber gibbosum is found in Oregon and Washington and is a mycorrhizal fungus with Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii.) It is important in the old growth forest ecosystem because it helps the Douglas fir tree to grow tall and strong by providing increased absorption of nutrients from the soil. The Oregon white truffle is also important as a food source: during certain times of the years more than 90% of the diet of the northern flying squirrel and other small rodents is made up of this species, as well as other truffles and false truffles. Of course these small rodents make up most of the diet of large birds, such as the endangered Northern Spotted owl. So Tuber gibbosum is important on several levels to the ecosystem.

The Oregon white truffle can also serve as a delicious food source for people. The flavor of the truffle is very difficult to describe, but once you have tasted it you will always recognize it. This fungus is not eaten as a regular mushroom, but is used for flavoring of soft cheeses, broiled meats, and rice. The flavor is very strong and only a small amount is needed. The flavoring agent is volatile and fat-soluble, so long cooking simply results in your kitchen smelling very good, but most of the flavor is lost.

Tuber gibbosum is a member of the Tuberales in the Discomycetes in the phylum Ascomycota. Most other Discomycetes have an epigeous (above ground) apothecium, an open ascocarp with the asci in a hymenium. However, the Tuberales have a hypogeous (below ground) ascocarp with scattered asci. The image on the left is a cross section of a truffle ascoma showing the distribution of the asci.

The species was first described by American mycologist Harvey Wilson Harkness in 1899. The specific epithet derives from the Latin word gibbosum meaning "humped", and refers to the irregular lobes and humps on larger specimens. T. gibbosum is part of the Gibbosum clade of the genus Tuber. Species in this clade have unusual "peculiar wall thickenings on hyphal tips emerging from the peridial surface at maturity."

Related species

There are a couple other species of Tuber in the Pacific Northwest, including the milder-tasting Tuber giganteum. The black truffle or Perigold truffle (Tuber melanosporum) grows primarily in Europe, especially Italy and France. In Italy trained pigs hunt for truffles with their owners, while French hunters usually use dogs (or so I've been told). There are various other genera of truffles and false truffles, including Gautieria, Elaphomyces, Geopora, Leucangium, and others. There are truffles and false truffles in all parts of the world, but not all species are edible. None are poisonous that we know of, but most don't have any real flavor. We have found truffles (genus Tuber) and false truffles (genus Elaphomyces) in Wisconsin on several Wisconsin Mycological Society forays. They appear to play a similar although less dramatic role in eastern ecosystems.

References:Tom Volk's Fungus of the Month