NAME(S)

TAXONOMY

PLANTAE ID

THERAPEUTIC

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Liriodendron tulipifera

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Liriodendron tulipifera

United States

Issued:

Stamp:

Liriodendron tulipifera

Genus species (Plantae): Liriodendron tulipifera

Liriodendron tulipifera—known as the tulip tree, American tulip tree, tulipwood, tuliptree, tulip poplar, whitewood, fiddletree, lynn-tree, hickory-poplar, and yellow-poplar—is the North American representative of the two-species genus Liriodendron (the other member is Liriodendron chinense), and the tallest eastern hardwood. It is native to eastern North America from Southern Ontario and possibly southern Quebec to Illinois eastward to southwestern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and south to central Florida and Louisiana. It can grow to more than 50 m (160 ft) in virgin cove forests of the Appalachian Mountains, often with no limbs until it reaches 25–30 m (80–100 ft) in height, making it a very valuable timber tree. The tallest individual at the present time (2021) is one called the Fork Ridge Tulip Tree at a secret location in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. Repeated measurements by laser and tape-drop have shown it to be 191 feet 10 inches (58.47 m) in height. This is the tallest known individual tree in eastern North America.

It is fast-growing, without the common problems of weak wood strength and short lifespan often seen in fast-growing species. April marks the start of the flowering period in the Southern United States (except as noted below); trees at the northern limit of cultivation begin to flower in June. The flowers are pale green or yellow (rarely white), with an orange band on the tepals; they yield large quantities of nectar. The tulip tree is the state tree of Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Description

The tulip tree is one of the largest of the native trees of eastern North America, known in an extraordinary case to reach the height of 58.5 m (192 ft) with the next-tallest known specimens in the 52–54 m (170–177 ft) range. These heights are comparable to the very tallest known eastern white pines, another species often described as the tallest in eastern North America.

The trunk on large examples is typically 1.2–1.8 m (4–6 ft) in diameter, though it can grow much broader. Its ordinary height is 24–46 m (80–150 ft) and it tends to have a pyramidal crown. It prefers deep, rich, and rather moist soil; it is common throughout the Southern United States. Growth is fairly rapid.

The bark is brown, furrowed, aromatic and bitter. The branchlets are smooth, and lustrous, initially reddish, maturing to dark gray, and finally brown. The wood is light yellow to brown, and the sapwood creamy white; light, soft, brittle, close, straight-grained. Specific gravity: 0.4230; density: 422 g/dm3 (26.36 lb/cu ft).

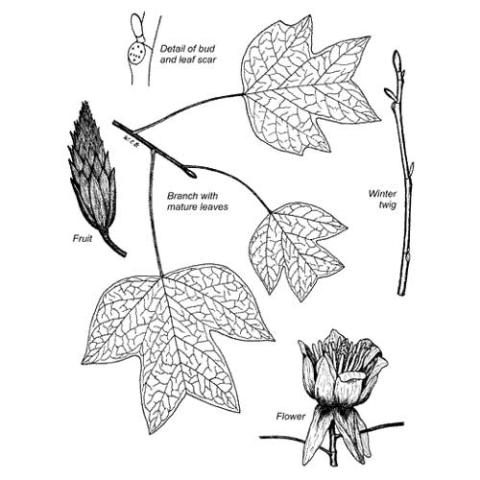

Winter buds are dark red, covered with a bloom, obtuse; scales becoming conspicuous stipules for the unfolding leaf, and persistent until the leaf is fully grown. Flower-bud enclosed in a two-valved, caducous bract.

The alternate leaves are simple, pinnately veined, measuring 125–150 mm (5–6 in) long and wide. They have four lobes, and are heart-shaped or truncate or slightly wedge-shaped at base, entire, and the apex cut across at a shallow angle, making the upper part of the leaf look square; midrib and primary veins prominent. They come out of the bud recurved by the bending down of the petiole near the middle bringing the apex of the folded leaf to the base of the bud, light green, when full grown are bright green, smooth and shining above, paler green beneath, with downy veins. In autumn they turn a clear, bright yellow. Petiole long, slender, angled.

- Flowers: May. Perfect, solitary, terminal, greenish yellow, borne on stout peduncles, 40–50 mm (1+1⁄2–2 in) long, cup-shaped, erect, conspicuous. The bud is enclosed in a sheath of two triangular bracts which fall as the blossom opens.

- Calyx: Sepals three, imbricate in bud, reflexed or spreading, somewhat veined, early deciduous.

- Corolla: Cup-shaped, petals six, 50 mm (2 in) long, in two rows, imbricate, hypogynous, greenish yellow, marked toward the base with yellow. Somewhat fleshy in texture.

- Stamens: Indefinite, imbricate in many ranks on the base of the receptacle; filaments thread-like, short; anthers extrorse, long, two-celled, adnate; cells opening longitudinally.

- Pistils: Indefinite, imbricate on the long slender receptacle. Ovary one-celled; style acuminate, flattened; stigma short, one-sided, recurved; ovules two.

- Fruit: Narrow light brown cone, formed from many samaras which are dispersed by wind, leaving the axis persistent all winter. September, October.

Taxonomy

Originally described by Carl Linnaeus, Liriodendron tulipifera is one of two species (see also L. chinense) in the genus Liriodendron in the magnolia family. The name Liriodendron is Greek for "lily tree". It is also called the tuliptree Magnolia, or sometimes, by the lumber industry, as the tulip-poplar or yellow-poplar. However, it is not closely related to true lilies, tulips or poplars.

The tulip tree has impressed itself upon popular attention in many ways, and consequently has many common names. The tree's traditional name in the Miami-Illinois language is oonseentia. Native Americans so habitually made their dugout canoes of its trunk that the early settlers west of the Appalachian Mountains called it Canoewood. The color of its wood gives it the name Whitewood. In areas near the Mississippi River it is called a poplar largely because of the fluttering habits of its leaves, in which it resembles trees of that genus. It is sometimes called "fiddle tree," because its peculiar leaves, with their arched bases and in-cut sides, suggest the violin shape.

The external resemblance of its flowers to tulips named it the Tulip-tree. In their internal structure, however, they are quite different. Instead of the triple arrangements of stamens and pistil parts, they have indefinite numbers arranged in spirals.

Ecology

Liriodendron tulipifera is generally considered to be a shade-intolerant species that is most commonly associated with the first century of forest succession. In Appalachian forests, it is a dominant species during the 50–150 years of succession, but is absent or rare in stands of trees 500 years or older. One particular group of trees survived in the grounds of Orlagh College, Dublin for 200 years, before having to be cut down in 1990. On mesic, fertile soils, it often forms pure or nearly pure stands. It can and does persist in older forests when there is sufficient disturbance to generate large enough gaps for regeneration. Individual trees have been known to live for up to around 500 years.

All young tulip trees and most mature specimens are intolerant of prolonged inundation; however, a coastal plain swamp ecotype in the southeastern United States is relatively flood-tolerant. This ecotype is recognized by its blunt-lobed leaves, which may have a red tint. Liriodendron tulipifera produces a large amount of seed, which is dispersed by wind. The seeds typically travel a distance equal to 4–5 times the height of the tree, and remain viable for 4–7 years. The seeds are not one of the most important food sources for wildlife, but they are eaten by a number of birds and mammals.

Vines, especially wild grapevines, are known to be extremely damaging to young trees of this species. Vines are damaging both due to blocking out sunlight, and increasing weight on limbs which can lead to bending of the trunk and/or breaking of limbs.

Host plant

In terms of its role in the ecological community, L. tulipifera does not host a great diversity of insects, with only 28 species of moths associated with the tree. Among specialists, L. tulipifera is the sole host plant for the caterpillars of C. angulifera, a giant silkmoth found in the eastern United States. Several generalist species use L. tulipifera. It is a well-known host for the large, green eggs of the Papilio glaucus, the eastern tiger swallowtail butterfly, which are known to lay their eggs exclusively among plants in the magnolia and rose families of plants, primarily in mid-late June through early August, in some states.

Use

Liriodendron tulipifera is cultivated, and grows readily from seeds. These should be sown in fine soft soil in a cool and shady area. If sown in autumn they come up the succeeding spring, but if sown in spring they often remain a year in the ground. John Loudon noted that seeds from the highest branches of old trees are most likely to germinate. It is readily propagated from cuttings and easily transplanted.

Reference: Wikipedia, pfaf.org, learnaboutnature.com