Pinus contorta

Common name:

Lodgepole pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus strobus

Common name:

Eastern white pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Larix decidua

Common name:

European Larch

Genus:

Larix

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Abies balsamea

Common name:

Balsam fir

Genus:

Abies

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Picea abies

Common name:

Norway spruce

Genus:

Picea

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus ponderosa

Common name:

Ponderosa pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus contorta

Common name:

Lodgepole pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus strobus

Common name:

Eastern white pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Larix decidua

Common name:

European Larch

Genus:

Larix

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Abies balsamea

Common name:

Balsam fir

Genus:

Abies

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Picea abies

Common name:

Norway spruce

Genus:

Picea

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus ponderosa

Common name:

Ponderosa pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus contorta

Common name:

Lodgepole pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus strobus

Common name:

Eastern white pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Larix decidua

Common name:

European Larch

Genus:

Larix

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Abies balsamea

Common name:

Balsam fir

Genus:

Abies

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Picea abies

Common name:

Norway spruce

Genus:

Picea

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

Pinus ponderosa

Common name:

Ponderosa pine

Genus:

Pinus

Family:

Pinaceae

Order:

Pinales

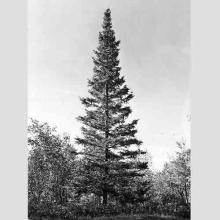

Family (Plantae): Pinaceae

The Pinaceae, pine family, are conifer trees or shrubs, including many of the well-known conifers of commercial importance such as cedars, firs, hemlocks, larches, pines and spruces. The family is included in the order Pinales, formerly known as Coniferales. Pinaceae are supported as monophyletic by their protein-type sieve cell plastids, pattern of proembryogeny, and lack of bioflavonoids. They are the largest extant conifer family in species diversity, with between 220 and 250 species (depending on taxonomic opinion) in 11 genera, and the second-largest (after Cupressaceae) in geographical range, found in most of the Northern Hemisphere, with the majority of the species in temperate climates, but ranging from subarctic to tropical. The family often forms the dominant component of boreal, coastal, and montane forests. One species, Pinus merkusii, grows just south of the equator in Southeast Asia. Major centers of diversity are found in the mountains of southwest China, Mexico, central Japan, and California.

Description

Members of the family Pinaceae are trees (rarely shrubs) growing from 2 to 100 m (7 to 300 ft) tall, mostly evergreen (except the deciduous Larix and Pseudolarix), resinous, monoecious, with subopposite or whorled branches, and spirally arranged, linear (needle-like) leaves. The embryos of Pinaceae have three to 24 cotyledons.

The female cones are large and usually woody, 2–60 cm (1–24 in) long, with numerous spirally arranged scales, and two winged seeds on each scale. The male cones are small, 0.5–6.0 cm (0.2–2 in) long, and fall soon after pollination; pollen dispersal is by wind. Seed dispersal is mostly by wind, but some species have large seeds with reduced wings, and are dispersed by birds. Analysis of Pinaceae cones reveals how selective pressure has shaped the evolution of variable cone size and function throughout the family. Variation in cone size in the family has likely resulted from the variation of seed dispersal mechanisms available in their environments over time. All Pinaceae with seeds weighing less than 90 mg are seemingly adapted for wind dispersal. Pines having seeds larger than 100 mg are more likely to have benefited from adaptations that promote animal dispersal, particularly by birds. Pinaceae that persist in areas where tree squirrels are abundant do not seem to have evolved adaptations for bird dispersal.

Boreal conifers have many adaptions for winter. The narrow conical shape of northern conifers, and their downward-drooping limbs help them shed snow, and many of them seasonally alter their biochemistry to make them more resistant to freezing, called "hardening".

Reference: Wikipedia