NAMES

TAXONOMY

FUNGI ID

THERAPEUTIC

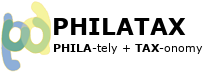

Ukraine

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

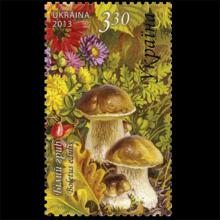

Mongolia

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

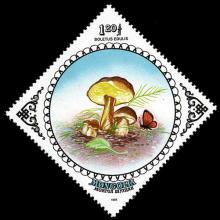

Hungary

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

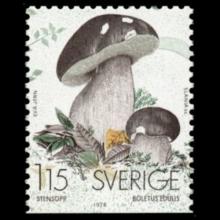

Sweden

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Bulgaria

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Ukraine

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Mongolia

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Hungary

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Sweden

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Bulgaria

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Ukraine

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Mongolia

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Hungary

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Sweden

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Bulgaria

Issued:

Stamp:

Boletus edulis

Altitude record for porcini mushrooms

by ETH Zurich, July 2, 2019

ETH researchers have discovered Boletus edulis (porcini mushrooms) growing at an elevation of over 2,400 metres in the Lower Engadine—the highest altitude ever recorded for these popular edible mushrooms in the Alps. Moreover, the mushrooms have "hooked up" with a new plant partner that was not on their list of possible symbionts to date.

A handful of students and their supervisors, Adrian Leuchtmann and Artemis Treindl, were truly astonished in September 2016 when they discovered Boletus edulis—an edible fungus commonly known as penny bun, cep or porcini mushroom—growing in the area above Scuol, in the Lower Engadine. They hadn't expected to find this species thriving at such an altitude, in the middle of the Motta Naluns ski area, 2,440 metres above sea level.

"We came across the mushrooms by chance," Treindl says. For several years Leuchtmann, Professor at the Institute of Integrative Biology, and Treindl have conducted a field course with biology and environmental sciences students in Scuol (Graubünden). On one of the excursions they take the students to explore the alpine zone above the timberline. The fact that Treindl stumbled upon porcini mushrooms that very day was a lucky coincidence, not the result of a specific search. "The fruiting bodies of the fungus don't necessarily appear at the same time every year, but we're always there at the end of August," she says.

Highest known site in the Alps

This find marks the altitude record for B. edulis in the Alps. Until now, its highest recorded occurrences were at 2,200 metres above sea level in Ticino and in Austria. The only place this fungus is known to grow at a higher altitude than in the Lower Engadine is in the Rocky Mountains, where porcini mushrooms have been found at elevations as high as 3,500 metres.

Moreover, it wasn't just the altitude that made the Lower Engadine find surprising. The Motta Naluns porcini mushrooms have "hooked up" with a mycorrhizal partner not previously recorded for this species of fungus: the dwarf willow Salix herbacea.

Many fungi form symbiotic partnerships with plants. The fungus produces mycelium, a web of fine filaments in the soil and around the root tips of the plant. This enables it to provide water and nutrients to the plant, as well as warding off harmful fungi and soil organisms. In return, the fungus receives carbohydrates such as sugars, which the plant produces via photosynthesis.

Successful switch to a new symbiont

B. edulis is not particularly picky when it comes to the choice of plant partners and will associate with various large deciduous and coniferous trees. However, the dwarf willow was previously not a known mycorrhizal partner for this fungus—at least, not in its core distribution range. This dwarf shrub is well adapted to the harsh mountain environment, growing horizontally underground with mostly just its leaves and blossoms visible above ground.

"It's likely that the porcini mushrooms in Motta Naluns shifted to the dwarf willow out of lack of more suitable alternatives," Leuchtmann says. Back in the lab, the two researchers confirmed that the host plant for the fungus was indeed the dwarf willow by analyzing fungal DNA they had isolated from the dwarf willow's root tips.

It is not clear how the fungus reached this unexpected altitude or how it managed to switch hosts. It might be that the wind carried spores from nearby colonies; alternatively, this colony might be a relic of earlier times when the timberline was much higher than it is today. In parts of the Alps, the timberline lies well below its natural height because humans have cut down forest to open up land for pasture. B. edulis's ability to colonize and survive at higher altitudes may also be a result of global warming.

Treindl and Leuchtmann want to study the Lower Engadine porcini mushrooms in more detail to get to the bottom of these and other unanswered questions. They are keen to discover whether the fungus is genetically distinct from nearby B. edulis colonies below the timberline. The ETH researchers would like to find out how closely the different populations are related to each other and whether the DNA of these alpine porcini mushrooms has changed compared to that of their forest-dwelling relatives.

Genus species (Fungi): Boletus edulis

Boletus edulis (English: cep, penny bun, porcino or porcini) is a basidiomycete fungus, and the type species of the genus Boletus. Widely distributed in the Northern Hemisphere across Europe, Asia, and North America, it does not occur naturally in the Southern Hemisphere, although it has been introduced to southern Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Brazil. Several closely related European mushrooms formerly thought to be varieties or forms of B. edulis have been shown using molecular phylogenetic analysis to be distinct species, and others previously classed as separate species are conspecific with this species. The western North American species commonly known as the California king bolete (Boletus edulis var. grandedulis) is a large, darker-coloured variant first formally identified in 2007.

The fungus grows in deciduous and coniferous forests and tree plantations, forming symbiotic ectomycorrhizal associations with living trees by enveloping the tree's underground roots with sheaths of fungal tissue. The fungus produces spore-bearing fruit bodies above ground in summer and autumn. The fruit body has a large brown cap which on occasion can reach 35 cm (14 in) in diameter and 3 kg (6.6 lb) in weight. Like other boletes, it has tubes extending downward from the underside of the cap, rather than gills; spores escape at maturity through the tube openings, or pores. The pore surface of the B. edulis fruit body is whitish when young, but ages to a greenish-yellow. The stout stipe, or stem, is white or yellowish in color, up to 25 cm (10 in) tall and 10 cm (4 in) thick, and partially covered with a raised network pattern, or reticulations.

Prized as an ingredient in various culinary dishes, B. edulis is an edible mushroom held in high regard in many cuisines, and is commonly prepared and eaten in soups, pasta, or risotto. The mushroom is low in fat and digestible carbohydrates, and high in protein, vitamins, minerals and dietary fibre. Although it is sold commercially, it is very difficult to cultivate. Available fresh in autumn in Central, Southern and Northern Europe, it is most often dried, packaged and distributed worldwide. It keeps its flavor after drying, and it is then reconstituted and used in cooking. B. edulis is one of the few fungi sold pickled.

Reference: Wikipedia