NAMES

TAXONOMY

FUNGI ID

THERAPEUTIC

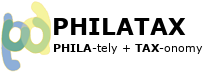

Switzerland

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Mongolia

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

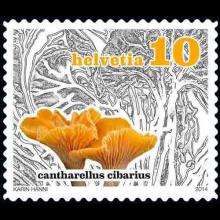

Hungary

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

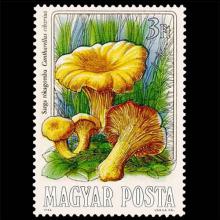

Sweden

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Switzerland

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Mongolia

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Hungary

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Sweden

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Switzerland

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Mongolia

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Hungary

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Sweden

Issued:

Stamp:

Cantharellus cibarius

Searching for Chanterelles, Nature's Edible Gold

by: Danielle Prewett,August 8, 2020

In the U.S., wild mushrooms have earned a reputation for being rare ingredients reserved for fine dining. I was reminded of this when I popped into a gourmet grocery store to buy artisanal oil and vinegar. The doors opened into a robust produce section filled with a variety of heirloom vegetables. I spotted the refrigerated wall lined with baskets of wild mushrooms. Chanterelles were $40 a pound; morels were $60! I walked right past them with a smirk on my face, knowing that two pounds were already sitting in my fridge. It felt good to have that edible gold sitting in my fridge, foraged for a fraction of the cost.

Chanterelles are beautiful mushrooms that form delicate, funnel-shaped caps as they age. They're prized for their subtle fruity and earthy flavors. Their texture is firm, especially when picked young. Unfortunately their freshness fades quickly. They turn bland, dry, and woody if not eaten within a few days.

Like morels, chanterelles have a symbiotic relationship with trees and cannot be cultivated commercially. They must be foraged in the wild, handled gently, and consumed quickly. This is why they come at a high price.

Luckily, there are dozens of different varieties growing abundantly in hardwood forests all across the country. Warm weather and consistent rain provide the right conditions for this particular fungus to fruit. And more than that, there's no better time to hike through the woods than summer.

In anticipation of these delicate, golden mushrooms, I'd been following the weather radar for a few weeks, waiting for a heavy downpour to alleviate our dry streak. Finally, after a few days of substantial rain, the moment was right. I drove to a national forest an hour away from home, carrying with me a backpack for water, a pocket knife, and a mesh bag for collecting. There was no one else on the trail, and I lost cell service. But—then and always—being out there gave me the subtle feeling that life had slowed down magically. The peace and quiet offered a breath of fresh air from the bustling metroplex where I live. In my mind, this factor alone should qualify as a modern luxury.

I began my search around creeks and in low spots where moisture collects. Some chanterelles are only the size of a quarter, but their vivid colors give themselves away.

I spotted a fiery red mushroom on the ground just a few feet from the path. It signaled where the others were, and soon I saw them strung across the ground in a row as if they were purposefully trying to lure me deeper into the woods.

Before harvesting, it's crucial to identify mushrooms with 100 percent certainty, so not to mistake them for a toxic lookalike. Typically, I refer to a mushroom field guide co-written by David Lewis, a renowned Mycologist in the Gulf Coast region where I live. I ran through a checklist: Was it growing on live or dead wood? No, chanterelles always grow on the ground. Did it have true gills? No, the underside of the cap should have “false gills,” or blunt ridges running down and onto the stem. These ridges should also always have a distinct fork in their path. Were the insides of the stem pale and shreddable? Yes, the flesh of the stem should be cream colored and pull apart like string cheese.

I confirmed the one in my hand was a cinnabar, a variety of chanterelle that's peppery in flavor and small in size, but retains its texture and shape well when cooked. I used my pocket knife to snip the stem free and tucked it into my bag. By the end of the day, my collection included two other varieties. I found the common golden chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) popular for its sweet fragrance; plus a large, smooth-ridged variety of chanterelle (Cantharellus lateritius) that has striking wavy edges, a pale yellow color, and a mild flavor.

What sets chanterelles apart from earthy porcinis or morels are their fruity, aromatic compounds. With a little imagination, you’ll find the mushrooms even smell like apricots. What’s even more fascinating is that stone fruits are coming into season at the same time. Coincidence? No. As unusual as it sounds, I believe nature intended for these two ingredients to complement each other. While mushrooms are often prepared in rich, fall-inspired recipes and rarely with summer in mind, I decided I would not miss the perfect opportunity to blend sweet and savory flavors together.

The apricots I bought recently at my local farmer's market came from the hill country, just a few hours away. They were perfectly ripe and ready to be eaten. I roughly chopped them and added them to a pot with caramelized shallots with ginger, honey, and chile flakes to simmer. This sweet and spicy spread I’ve created would pair well with the sautéed chanterelles. To round the meal out, I layered whipped goat cheese on top of toasted sourdough, and fresh arugula snipped from the garden.

As I dug into this golden stack, I immediately tasted the quality. These mushrooms and apricots would never be better than this brief moment when they were at the peak of their perfection. And for me, these perfectly fresh chanterelles weren’t the only things that made this dish truly special; it was also the time spent in the forest (click here for recipe).

Genus species (Fungi): Cantharellus cibarius

Cantharellus cibarius (Latin: cantharellus, "chanterelle"; cibarius, "culinary") is a species of golden chanterelle mushroom in the genus Cantharellus. It is also known as girolle (or girole). It grows in Europe from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean Basin, mainly in deciduous and coniferous forests. Due to its characteristic color and shape, it is easy to distinguish from mushrooms with potential toxicity that discourage human consumption. A commonly eaten and favored mushroom, the chanterelle is typically harvested from late summer to late fall in its European distribution.

Chanterelles are used in many culinary dishes, and can be preserved by either drying or freezing. An oven should not be used when drying it because can result in the mushroom becoming bitter.

Taxonomy

At one time, all yellow or golden chanterelles in North America had been classified as Cantharellus cibarius. Using DNA analysis, they have since been shown to be a group of related species known as the Cantharellus cibarius group or species complex, with C. cibarius sensu stricto restricted to Europe. In 1997, the Pacific golden chanterelle (C. formosus) and C. cibarius var. roseocanus were identified, followed by C. cascadensis in 2003 and C. californicus in 2008.

Description

The mushroom is easy to detect and recognize in nature. The body is 3–10 centimetres (1.2–3.9 in) wide and 5–10 centimetres (2.0–3.9 in) tall. The color varies from yellow to dark yellow. Red spots will appear on the cap of the mushroom if it is damaged. Chanterelle mushrooms have a faint aroma and flavour of apricots.

Care should be taken not to confuse this species with the deadly Omphalotus illudens.

Reference: Wikipedia

Photo: P. Needle.