NAMES

TAXONOMY

FUNGI ID

THERAPEUTIC

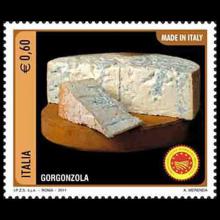

Italy

Issued:

Stamp:

Penicillium roqueforti

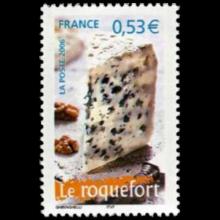

France

Issued:

Stamp:

Penicillium roqueforti

Italy

Issued:

Stamp:

Penicillium roqueforti

France

Issued:

Stamp:

Penicillium roqueforti

Italy

Issued:

Stamp:

Penicillium roqueforti

France

Issued:

Stamp:

Penicillium roqueforti

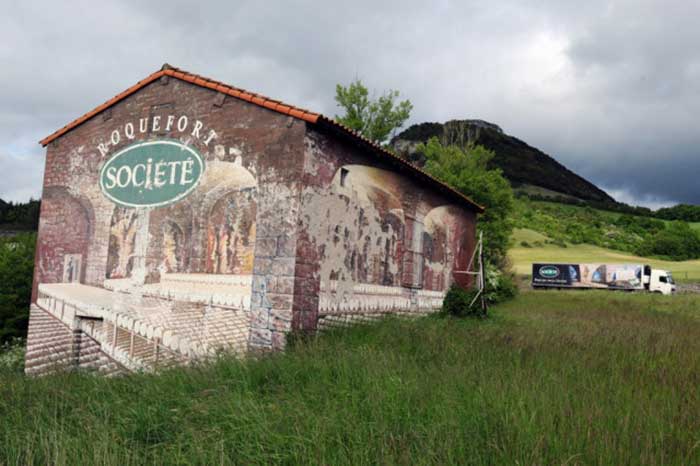

Roquefort: The story of the 600-year-old mouldy French cheese that heals wounds

This week, the small Occitan village of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, south of Millau, celebrates the anniversary of the charter granting them sole rights to make and sell their famous cheese.

While King Charles VI granted the village their monopoly on June 3rd 1411, the good people of Roquefort have been making their famously sharp, tangy dairy product for much, much longer.

Their secret? Well, legend tells of a shepherd who once saw, in the distance, a pretty young thing tending her own flock. Ditching his meal of sheep's cheese and bread in a cave, he went looking for her.

Unfortunately for him, but luckily for us, he was unsuccessful in wooing her, and when he returned, some time later, his cheese was riddled with a greenish mould. With nothing else to eat, he reluctantly took a bite of the cheese, only to discover a taste sensation.

The reality is probably far less romantic, but no less interesting. Turns out the cool, climatically-stable Combalou caves that the locals have used for centuries to mature their sheep's milk cheese are home to the Penicillium roqueforti mould, a fungus that loves nothing more than the nutrients found in maturing cheese. Riddling the wheels, it gives the distinct flavour that many have come to love.

(Also, if you're wondering about the name, an old folk remedy for open wounds in the region called for the cheese to be smeared over the injury. Turns out there was something to that!)

Over time, cheese makers have learned to work with the fungus, cultivating it on different mediums such as rye bread, before introducing it to the cheese. This has allowed further refining of the taste, to what we expect today.

Today, Roquefort's claim to the cheese is still fiercely protected. Nationally, it is subject to appellation d'origine contrôlée certification. Across Europe, naming rights are rigidly strict. Both the French certification, and EU legislation state that for a cheese to be considered 'Roquefort', it must be matured in the Combalou caves near the village, along with incredibly strict guidelines over ingredients and maturing times.

If you're a cheese addict, or just interested in a real French speciality, the caves in which the cheeses are matured can be visited on a guided tour, and yes, there is most certainly a tasting at the end of it, along with the opportunity to take a few wheels home.

In times such as these, take heart, dear reader - perhaps all that is needed is a cracker smeared with the king of cheeses!

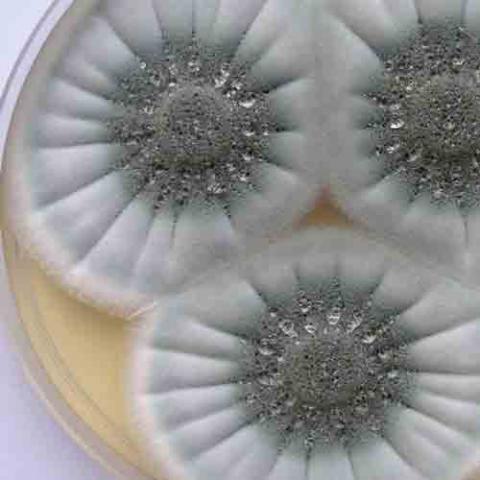

Genus species (Fungi): Penicillium roqueforti

First described by American mycologist Charles Thom in 1906, Penicillium roqueforti was initially a heterogeneous species of blue-green sporulating fungi. They were grouped into different species based on phenotypic differences, but later combined into one species by Kenneth B. Raper and Thom (1949). The Penicillium roqueforti group got a reclassification in 1996 thanks to molecular analysis of ribosomal DNA sequences. Formerly divided into two varieties ― cheese-making (Penicillium roqueforti var. roqueforti) and patulin-making (Penicillium roqueforti var. carneum) ― Penicillium roqueforti was reclassified into three species: Penicillium roqueforti, Penicillium carneum, and Penicillium paneum. The complete genome sequence of P. roqueforti was published in 2014.

Description

As this fungus does not form visible fruiting bodies, descriptions are based on macromorphological characteristics of fungal colonies growing on various standard agar media, and on microscopic characteristics. When grown on Czapek yeast autolysate (CYA) agar or yeast-extract sucrose (YES) agar, Penicillium roqueforti colonies are typically 40 mm in diameter, olive brown to dull green (dark green to black on the reverse side of the agar plate), with a velutinous texture. Grown on malt extract agar (MEA), colonies are 50 mm in diameter, dull green in color (beige to greyish green on the reverse side), with arachnoid (with many spider-web-like fibers) colony margins. Another characteristic morphological feature of this species includes the production of asexual spores in phialides with a distinctive brush-shaped configuration.

Evidence for a sexual stage in Penicillium roqueforti has been found based, in part, on the presence of functional mating type genes and most of the important genes known to be involved in meiosis. In 2014, researchers reported inducing the growth of sexual structures in Penicillium roqueforti, including ascogonia, cleistothecia and ascospores. Genetic analysis and comparison of many different strains isolated from various environments around the world indicate that it is a genetically diverse species.

Penicillium roqueforti is known to be one of the most common spoilage molds of silage. It is also one of several different moulds that can spoil bread.

Uses

The chief industrial use of this species is the production of blue cheeses, such as its namesake Roquefort, Bleu de Bresse, Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage, Brebiblu, Cabrales, Cambozola (Blue Brie), Cashel Blue, Danish blue, Fourme d'Ambert, Fourme de Montbrison, Lanark Blue, Shropshire Blue and Stilton, and some varieties of Bleu d'Auvergne and Gorgonzola. (Other blue cheeses, including Bleu de Gex and Rochebaron, use Penicillium glaucum.)

Strains of the microorganism are also used to produce compounds that can be employed as antibiotics, flavours, and fragrances (Sharpell, 1985), uses not regulated under the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). Its texture is chitinous.

Secondary metabolites

Considerable evidence indicates that most strains are capable of producing harmful secondary metabolites (alkaloids and other mycotoxins) under certain growth conditions. Aristolochene is a sesquiterpenoid compound produced by Penicillium roqueforti, and is likely a precursor to the toxin known as PR toxin, made in large amounts by the fungus. PR-toxin has been implicated in incidents of mycotoxicoses resulting from eating contaminated grains. However, PR toxin is not stable in cheese and breaks down to the less toxic PR imine.

Secondary metabolites of P. roqueforti, named andrastins A-D, are found in blue cheese. The andrastins inhibit proteins involved in the efflux of anticancer drugs from multidrug-resistant cancer cells.

Penicillium roqueforti also produces the neurotoxin roquefortine C. However the levels of roquefortine c in cheese made from Penicillium Roqueforti is usually too low to produce toxic effects. The organism can also be used for the production of proteases and specialty chemicals, such as methyl ketones including 2-heptanone.

Reference: Wikipedia, www.mnhn.fr