Aenocyon dirus

Common name:

Dire wolf

Genus:

Aenocyon

Family:

Canidae

Suborder:

-n/a-

Aenocyon dirus

Common name:

Dire wolf

Genus:

Aenocyon

Family:

Canidae

Suborder:

-n/a-

Aenocyon dirus

Common name:

Dire wolf

Genus:

Aenocyon

Family:

Canidae

Suborder:

-n/a-

Genus (Animalia): Aenocyon

Description

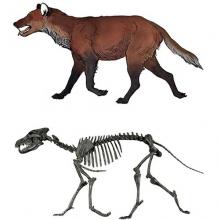

The dire wolf was once thought to be the largest species of the genus Canis known to have existed, though genetic analysis in 2021 strongly suggests it belongs to its own genus; Aenocyon, showing that its similarities to true wolves were merely a case of convergent evolution. Its shape and proportions were similar to those of two modern North American wolves: the Yukon wolf (Canis lupus pambasileus) and the Northwestern wolf (Canis lupus occidentalis). The largest northern wolves today have a shoulder height of 38 in (97 cm) and a body length of 69 in (180 cm). Some dire wolf specimens from Rancho La Brea are smaller than this, and some are larger.

The dire wolf had smaller feet and a larger head when compared with a northern wolf of the same body size. The skull length could reach up to 310 mm (12 in) or longer, with a broader palate, frontal region, and zygomatic arches compared with the Yukon wolf. These dimensions make the skull very massive. Its sagittal crest was higher, with the inion showing a significant backward projection, and with the rear ends of the nasal bones extending relatively far back into the skull. A connected skeleton of a dire wolf from Rancho La Brea is difficult to find because the tar allows the bones to disassemble in many directions. Parts of a vertebral column have been assembled, and it was found to be similar to that of the modern wolf, with the same number of vertebrae.

Geographic differences in dire wolves were not detected until 1984, when a study of skeletal remains showed differences in a few cranio-dental features and limb proportions between specimens from California and Mexico (A. d. guildayi) and those found from the east of the Continental Divide (A. d. dirus). A comparison of limb size shows that the rear limbs of C. d. guildayi were 8% shorter than the Yukon wolf due to a significantly shorter tibia and metatarsus, and that the front limbs were also shorter due to their slightly shorter lower bones. With its comparatively lighter and smaller limbs and massive head, A. d. guildayi was not as well adapted for running as timber wolves and coyotes. A. d. dirus possessed significantly longer limbs than A. d. guildayi. The forelimbs were 14% longer than A. d. guildayi due to 10% longer humeri, 15% longer radii, and 15% longer metacarpals. The rear limbs were 10% longer than A. d. guildayi due to 10% longer femora and tibiae, and 15% longer metatarsals. A. d. dirus is comparable to the Yukon wolf in limb length. The largest A. d. dirus femur was found in Carroll Cave, Missouri, and measured 278 mm (10.9 in).

Prey

A range of animal and plant specimens that became entrapped and were then preserved in tar pits have been removed and studied so that researchers can learn about the past. The Rancho La Brea tar pits located near Los Angeles in southern California are a collection of pits of sticky asphalt deposits that differ in deposition time from 40,000 to 12,000 YBP. Commencing 40,000 YBP, trapped asphalt has been moved through fissures to the surface by methane pressure, forming seeps that can cover several square meters and be 9–11 m (30–36 ft) deep. The dire wolf has been made famous because of the large number of its fossils recovered there. Over 200,000 specimens (mostly fragments) have been recovered from the tar pits, with the remains ranging from Smilodon to squirrels, invertebrates, and plants. The time period represented in the pits includes the Last Glacial Maximum when global temperatures were 8 °C (14 °F) lower than today, the Pleistocene–Holocene transition (Bølling-Allerød interval), the Oldest Dryas cooling, the Younger Dryas cooling from 12,800 to 11,500 YBP, and the American megafaunal extinction event 12,700 YBP when 90 genera of mammals weighing over 44 kg (97 lb) became extinct.

Isotope analysis can be used to identify some chemical elements, allowing researchers to make inferences about the diet of the species found in the pits. An isotope analysis of bone collagen extracted from La Brea specimens provides evidence that the dire wolf, Smilodon, and the American lion (Panthera leo atrox) competed for the same prey. Their prey included "yesterday's camel" (Camelops hesternus), the Pleistocene bison (Bison antiquus), the "dwarf" pronghorn (Capromeryx minor), the western horse (Equus occidentalis), and the "grazing" ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani) native to North American grasslands. The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) and the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) were rare at La Brea. The horses remained mixed feeders and the pronghorns mixed browsers, but at the Last Glacial Maximum and its associated shift in vegetation the camels and bison were forced to rely more heavily on conifers.

A study of isotope data of La Brea dire wolf fossils dated 10,000 YBP provides evidence that the horse was an important prey species at the time, and that sloth, mastodon, bison, and camel were less common in the dire wolf diet. This indicates that the dire wolf was not a prey specialist, and at the close of the late Pleistocene before its extinction it was hunting or scavenging the most available herbivores.

Reference: Wikipedia