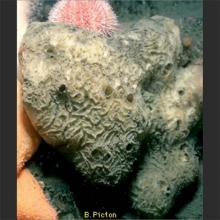

Mycale lingua

Common name:

(none found)

Class:

Demospongiae

Subphylum:

Phylum:

Porifera

Mycale lingua

Common name:

(none found)

Class:

Demospongiae

Subphylum:

Phylum:

Porifera

Mycale lingua

Common name:

(none found)

Class:

Demospongiae

Subphylum:

Phylum:

Porifera

Phylum (Animalia): Porifera

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (/pəˈrɪfərə/; meaning "pore bearer"), are a basal Metazoa (animal) clade as a sister of the Diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through them, consisting of jelly-like mesohyl sandwiched between two thin layers of cells. The branch of zoology that studies sponges is known as spongiology.

Sponges have unspecialized cells that can transform into other types and that often migrate between the main cell layers and the mesohyl in the process. Sponges do not have nervous, digestive or circulatory systems. Instead, most rely on maintaining a constant water flow through their bodies to obtain food and oxygen and to remove wastes. Sponges were first to branch off the evolutionary tree from the common ancestor of all animals, making them the sister group of all other animals.

Etymology

The term sponge derives from the Ancient Greek word σπόγγος (spóngos).

Overview

Sponges are similar to other animals in that they are multicellular, heterotrophic, lack cell walls and produce sperm cells. Unlike other animals, they lack true tissues and organs. Some of them are radially symmetrical, but most are asymmetrical. The shapes of their bodies are adapted for maximal efficiency of water flow through the central cavity, where the water deposits nutrients and then leaves through a hole called the osculum. Many sponges have internal skeletons of spongin and/or spicules (skeletal-like fragments) of calcium carbonate or silicon dioxide. All sponges are sessile aquatic animals, meaning that they attach to an underwater surface and remain fixed in place (i.e., do not travel). Although there are freshwater species, the great majority are marine (salt-water) species, ranging in habitat from tidal zones to depths exceeding 8,800 m (5.5 mi).

Although most of the approximately 5,000–10,000 known species of sponges feed on bacteria and other microscopic food in the water, some host photosynthesizing microorganisms as endosymbionts, and these alliances often produce more food and oxygen than they consume. A few species of sponges that live in food-poor environments have evolved as carnivores that prey mainly on small crustaceans.

Most species use sexual reproduction, releasing sperm cells into the water to fertilize ova that in some species are released and in others are retained by the "mother." The fertilized eggs develop into larvae, which swim off in search of places to settle. Sponges are known for regenerating from fragments that are broken off, although this only works if the fragments include the right types of cells. A few species reproduce by budding. When environmental conditions become less hospitable to the sponges, for example as temperatures drop, many freshwater species and a few marine ones produce gemmules, "survival pods" of unspecialized cells that remain dormant until conditions improve; they then either form completely new sponges or recolonize the skeletons of their parents.

In most sponges, an internal gelatinous matrix called mesohyl functions as an endoskeleton, and it is the only skeleton in soft sponges that encrust such hard surfaces as rocks. More commonly, the mesohyl is stiffened by mineral spicules, by spongin fibers, or both. Demosponges use spongin; many species have silica spicules, whereas some species have calcium carbonate exoskeletons. Demosponges constitute about 90% of all known sponge species, including all freshwater ones, and they have the widest range of habitats. Calcareous sponges, which have calcium carbonate spicules and, in some species, calcium carbonate exoskeletons, are restricted to relatively shallow marine waters where production of calcium carbonate is easiest. The fragile glass sponges, with "scaffolding" of silica spicules, are restricted to polar regions and the ocean depths where predators are rare. Fossils of all of these types have been found in rocks dated from 580 million years ago. In addition Archaeocyathids, whose fossils are common in rocks from 530 to 490 million years ago, are now regarded as a type of sponge.

The single-celled choanoflagellates resemble the choanocyte cells of sponges which are used to drive their water flow systems and capture most of their food. This along with phylogenetic studies of ribosomal molecules have been used as morphological evidence to suggest sponges are the sister group to the rest of animals. Some studies have shown that sponges do not form a monophyletic group, in other words do not include all and only the descendants of a common ancestor. Recent phylogenetic analyses suggested that comb jellies rather than sponges are the sister group to the rest of animals. However reanalysis of the data showed that the computer algorithms used for analysis were misled by the presence of specific ctenophore genes that were markedly different from those of other species, leaving sponges as either the sister group to all other animals, or an ancestral paraphyletic grade.

The few species of demosponge that have entirely soft fibrous skeletons with no hard elements have been used by humans over thousands of years for several purposes, including as padding and as cleaning tools. By the 1950s, though, these had been overfished so heavily that the industry almost collapsed, and most sponge-like materials are now synthetic. Sponges and their microscopic endosymbionts are now being researched as possible sources of medicines for treating a wide range of diseases. Dolphins have been observed using sponges as tools while foraging.

Distinguishing Features

Sponges constitute the phylum Porifera, and have been defined as sessile metazoans (multicelled immobile animals) that have water intake and outlet openings connected by chambers lined with choanocytes, cells with whip-like flagella. However, a few carnivorous sponges have lost these water flow systems and the choanocytes. All known living sponges can remold their bodies, as most types of their cells can move within their bodies and a few can change from one type to another.

Even if a few sponges are able to produce mucus – which acts as a microbial barrier in all other animals – no sponge with the ability to secrete a functional mucus layer has been recorded. Without such a mucus layer their living tissue is covered by a layer of microbial symbionts, which can contribute up to 40–50% of the sponge wet mass. This inability to prevent microbes from penetrating their porous tissue could be a major reason why they have never evolved a more complex anatomy.

Like cnidarians (jellyfish, etc.) and ctenophores (comb jellies), and unlike all other known metazoans, sponges' bodies consist of a non-living jelly-like mass (mesohyl) sandwiched between two main layers of cells. Cnidarians and ctenophores have simple nervous systems, and their cell layers are bound by internal connections and by being mounted on a basement membrane (thin fibrous mat, also known as "basal lamina"). Sponges have no nervous systems, their middle jelly-like layers have large and varied populations of cells, and some types of cells in their outer layers may move into the middle layer and change their functions.

Reference: Wikipedia