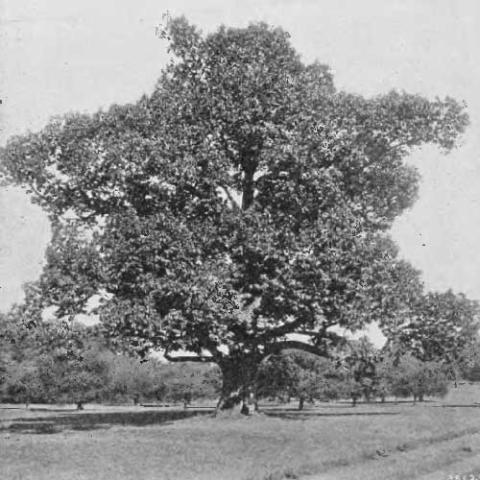

Castanea dentata is a rapidly-growing, large, deciduous hardwood dicot tree. Pre-blight sources give a maximum height of 115 feet (35 m), and a maximum circumference of 13 feet (4.0 m). Post-blight sources erroneously report a greater maximum size of the species compared with pre-blight, likely due to nostalgia, to interpretations of pre-blight measurements of circumference as being measurements of diameter, and to the misapprehension that pre-blight observations of maximum size represented observations of average size. It is considerably larger than the closely related Allegheny chinquapin (Castanea pumila).

There are several other chestnut species, such as the European sweet chestnut (C. sativa), Chinese chestnut (C. mollissima), and Japanese chestnut (C. crenata). Castanea dentata can be distinguished by a few morphological traits, such as petiole length, nut size and number of nuts per burr, leaf shape, and leaf size, with leaves being 14–20 cm (5.5–8 in) long and 7–10 cm (3–4 in) broad—slightly shorter and broader than the sweet chestnut. It has larger and more widely spaced saw-teeth on the edges of its leaves, as indicated by the scientific name dentata, Latin for "toothed".

The European sweet chestnut was introduced in the United States by Thomas Jefferson in 1773. The European sweet chestnut has hairy twig tips in contrast to the hairless twigs of the American chestnut. This species has been the chief source of commercial chestnuts in the United States. Japanese chestnut was inadvertently introduced into the United States by Thomas Hogg in 1876 and planted on the property of S. B. Parsons in Flushing, New York. The Japanese chestnut has narrow leaves, smaller than either American chestnut or sweet chestnut, with small, sharply-pointed teeth and many hairs on the underside of the leaf and is the most blight-resistant species.

The chestnut is monoecious, and usually protandrous producing many small, pale green (nearly white) male flowers found tightly occurring along 6 to 8 inch long catkins. The female parts are found near the base of the catkins (near twig) and appear in late spring to early summer. Like all members of the family Fagaceae, American chestnut is self-incompatible and requires two trees for pollination, which can be with other members of the Castanea genus. The pollen of the American chestnut is considered a mild allergen.

The American chestnut is a prolific bearer of nuts, beginning inflorescence and nut production in the wild when a tree is 8 to 10 years old. American chestnut burrs often open while still attached to the tree, around the time of the first frost in autumn, with the nuts then falling to the ground. American chestnut typically have three nuts enclosed in a spiny, green burr, each lined in a tan velvet. In contrast, the Allegheny chinquapin produces but one nut per burr.

Evolution and ecology

Chestnuts are in the Fagaceae family along with beech and oak. Chestnuts are not closely related to the horse chestnut, which is in the family Sapindaceae. Phylogenetic analysis indicates a westward migration of extant Castanea species from Asia to Europe to North America, with the American chestnut more closely related to the Allegheny chinquapin (Castanea pumila v. pumila) than to European or Asian clades. The genomic range of chestnuts can be roughly divided into a clinal pattern of northeast, central, and southwest populations, with southwest populations showing greatest diversity, reflecting an evolutionary bottleneck likely due to Quaternary glaciation. Two lineages of American chestnut have been identified, one a hybrid between the American chestnut and the Allegheny chinquapin from the southern Appalachians. The other lineage of American Chestnut shows a gradual loss of genetic diversity along a Northward vector, indicating possible expansion of range following the most recent Glacial Maximum during the Wisconsin glaciation. Ozark chinkapin, which is typically considered either a distinct species (C. ozarkensis) or a subspecies of the Allegheny chinquapin (C. pumila subsp. ozarkensis), may be ancestral to both the American chestnut and the Allegheny chinquapin. A natural hybrid of C. dentata and C. pumila has been named Castanea × neglecta.

The American chestnut population was reduced to 1–10% of its original size as a result of the chestnut blight and has not recovered. The surviving trees are "frozen in time" with shoots re-sprouting from survivor rootstock but almost entirely undergoing blight-induced dieback without producing chestnuts. Unexpectedly, American chestnut appears to have retained substantial genetic diversity following the population bottleneck, which is at odds with the limited incidence of blight resistance/tolerance in extant populations.

The pre-blight distribution of the American chestnut was restricted to moist, but well-drained, steep slopes with acid loam soils. According to analysis of old forest dust data, the tree was rare or absent in New England prior to 2,500 years before the present, but rapidly established dominance in these forests, becoming a common tree over a range from Maine and southern Ontario to Mississippi, and from the Atlantic coast to the Appalachian Mountains and the Ohio Valley. Within its range, the American chestnut was the dominant timber of mountain ridges and sandstone soils. Along the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, the American chestnut dominated the area above the range of the Eastern hemlock and below 1,500 meters. In Western Maryland, the American chestnut comprised 50% of ridge timber and 36% of forested slopes.

The tree's abundance was due to a combination of rapid growth, relative fire resistance, and a large annual nut crop, in comparison to oaks, which do not reliably produce sizable numbers of acorns every year. Fire was common in the pre-blight ecosystem of the American chestnut, perhaps in part due to unique traits of the tree, including fire tolerance, highly flammable litter, tall stature, rapid growth, and ability to resprout. Historically, the mean fire return interval was 20 years or less in chestnut-predominant ecologies, with a forest stand pattern that was more open than is currently the case.

The American chestnut was an important tree for wildlife, providing much of the fall mast for species such as white-tailed deer, wild turkey, Allegheny woodrat and (prior to its extinction) the passenger pigeon. Black bears were also known to eat the nuts to fatten up for the winter. The American chestnut also contains more nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium in its leaves than other trees that share its habitat, so they return more nutrients to the soil which helps with the growth of other plants, animals, and microorganisms. The American chestnut is preferred by some avian seed hoarders, and was particularly important as a food source during years where the oak mast failed.

Uses

Food

The nuts were once an important economic resource in North America, being sold on the streets of towns and cities, as they sometimes still are during the Christmas season (usually said to be "roasting on an open fire" because their smell is readily identifiable many blocks away). Chestnuts are edible raw or roasted, though typically preferred roasted. One must peel the brown skin to access the yellowish-white edible portion.

The nuts were commonly fed on by various types of wildlife and was also in such a high abundance that they were used to feed livestock by farmers, by allowing those livestock to roam freely into the forests that were predominantly filled with American chestnut trees.

The American chestnut tree was important to many Native American tribes in North America as it served as a food source, both for them and the wildlife they hunted, and also as a component in traditional medicine.